Speaking about the formation of the image of the Russian Middle Ages in Russian culture, it is necessary, first of all, to ask the question: at what point does the early Russian history begin to be perceived precisely as medieval? This question is not as simple as it might seem.

To date, there is no single periodization of the history of Russia. The terms “Kievan Rus”, “Domongolskaya Rus”, “Ancient Rus”, “Medieval Rus”, etc. are used to indicate its initial stage. Despite the apparent synonymy, each of them carries with it a number of related meanings.

Their chronological boundaries are also quite blurred. So, the period of “Kievan Rus” is conditionally limited by the collapse of a single centralized state at the beginning of the XII century. and the transfer of the capital of the great princes to Vladimir. The period of “pre-Mongol Rus” ends with the beginning of the Batu invasion in the winter of 1237–1238. As for the concept of “Ancient Rus”, it can acquire a variety of temporal characteristics. In a narrow sense, the “Old Russian period” is often equated with either Kiev or pre-Mongol. In a broad sense, it can be brought up to the end of the 17th century. (Especially often such a broad interpretation of “Ancient Russia” is found in literary and art criticism works).

The same ambiguous definition has “Medieval Russia”. On the one hand, this concept often denotes the period that began with the disintegration of the centralized state into specific principalities, as if coming to replace “Ancient Russia”. Moreover, from the point of view of West European periodization, formed in the IX century. the Russian state immediately turned out to be a medieval state. The upper border of the Russian “Middle Ages” is also blurred: it is localized by different researchers ranging from the completion of the unification of Russian lands around Moscow (end of the XV – beginning of the XVI century) to the Time of Troubles (beginning of the XVII century), and in some cases even before the Petrine reforms (beginning of the XVIII century). In addition, quite often the phrases “Ancient Russia” and “Medieval Russia” appear as interchangeable synonyms.

All this terminological confusion arose in historiography literally over the past century and a half. Prior to this, the concept of “Medieval Russia” did not exist at all, and the word “antiquity” was used almost exclusively to denote the Russian past. And the image of this “Russian antiquity” was noticeably different from the image of the “Russian Middle Ages.”

Where does antiquity end?

In different historical eras, the understanding of the boundaries of “ancient” and “new” has constantly changed. After the baptism of Rus, Russian culture adopted common Christian historical ideas, according to which human history was understood as a linear movement from Creation to the Last Judgment. The main event that divided its course into ancient (Old Testament) and new (New Testament) history was the coming of Jesus Christ into the world.

However, this division was almost immediately rethought in Russian book writing. Already in the ancient monument of Russian literature, “The Word of the Law and Grace” by Metropolitan Hilarion, we see that the boundary between the “ancient” and the “new” is not the Nativity of Christ, but the baptism of Russia – the birth of a new Christian people. “Blessed be the Lord Jesus Christ, even love the new people, Ruska earth, and enlighten you with holy baptism,” it was said in The Tale of Bygone Years.

In the future, the border between the “ancient” (“old”) and the “new” times, which is quite clearly recognized by Russian scribes, is constantly shifting towards the present. After the collapse of the united Russian state into specific principalities, the former unity of Russia began to be perceived as “antiquity”. In the “Tale of Igor’s Campaign”, where the author contrasted the “old princes” with the “new princes”, the era of the reign of Vladimir and Yaroslav referred to the “ancient times”, and the period of fragmentation and strife to the “new” ones. There is no talk of any “average” times here.

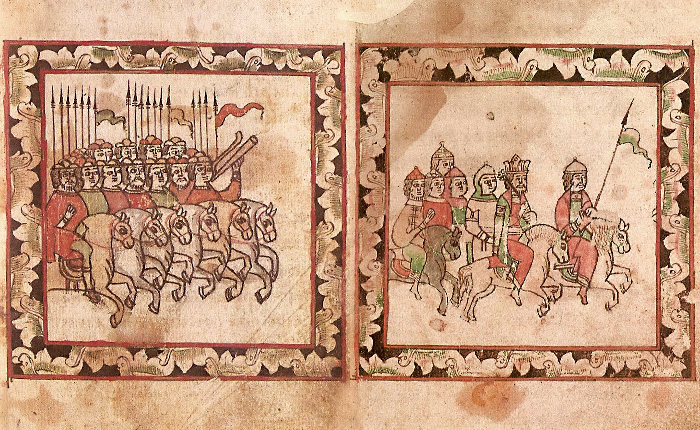

The new frontier, dividing Russian history into “before” and “after”, was the invasion of the Tatars. “Zadonshchina” ended the “first years of time” with the Kalatsky army (that is, with the battle of Kalka): “And the Russian land sits unhappily from the end.” Moreover, since the end of the XIV century. for the first time in Russian bookishness, ideas about the “trinity” of Russian history are formed: 1) ancient pre-Mongol Russia (a kind of “Golden Age”); 2) the “dark” time of the Horde yoke; 3) a new time, at the same time representing a return to “antiquity”. The transition to this “new” time was foreshadowed by the Battle of Kulikovo. “And from the Kalyatsky rati to Momaev the battle has been 160 years old,” the Zadonshchina said. With a certain degree of conventionality, these 160 years can be called the Russian Middle Ages, which was first designated in historical thought.

This concept was fully realized already in the era of Moscow Russia. The collection of land around Moscow was positioned as a return to former unity and prosperity. Moscow is perceived as a “second Kiev”, Moscow princes and kings as successors of Kiev princes. The idea of returning primordially Russian lands to the rule of Moscow sovereigns sounded right up to the annexation of Left-Bank Ukraine in the 17th century.

Thus, by the end of the XVII century. a three-part model of Russian history (in accordance with the mythological triad: “the light is dying out – the darkness is the light of rebirth”), as a whole, existed. But this concept will be almost completely erased from public thought by the reign of Peter, who will again divide Russian history into only two parts: “ancient”, pre-Petrine, and “new”, post-Petrine Russia.

“Russian antiquity”

XVIII century It was at the same time the beginning of Russian historical science and the beginning of a rethinking of historical events in Russian art. Despite the fact that the periodization of history adopted in Europe was well known in the Russian Empire in the 18th century. (and even V. N. Tatishchev himself, in advance of his “History”, noted that some divide it at times into “ancient”, “average” and “new”), it was not accepted by the first Russian historians. The Russian historical process, as a rule, was divided by them into periods during the rule of princes and tsars. Moreover, the definition of “antiquity” prevailed for its general characteristics. It is enough to look at the names of the historical works of this era: “Russian History from the Most Ancient Times” by V. N. Tatishchev, “Ancient Russian History” by M. V. Lomonosov, “Russian History from the Ancient Times” M.

At the same time, the image of Russian antiquity begins to take shape in fiction, painting and dramaturgy. Its embodiment in art is strongly influenced by the canons of classicism. Russian writers of this time did not set themselves the task of faithfully depicting historical reality. In their work, they relied on the “Poetics” of Aristotle and the traditions of the French theater of the era of classicism, and therefore Ancient Russia (or, more precisely, “Ancient Russia”) acquired numerous antique features in their image.

The plots of the first Russian tragedies themselves were often borrowed from the works of Voltaire, Cornel, Racine, and others, and were only transferred to Russian soil. “Khorev” by A. P. Sumarokov echoed Voltaire’s “Brutus”, “Olga” by Ya. B. Knyazhnin – with “Meropa”, etc. “Roman dresses” were used as costumes for staging performances, classical ones as decorations interiors with arches, columns and pilasters.

The opposite trend in the image of Russian antiquity in the art of the XVIII century. was her “modernization.” Already Feofan Prokopovich in the tragicomedy “Vladimir” (the first Russian dramatic work on a historical theme) attributed to Vladimir the features of Peter I, and compared the baptism of Russia with the Petrine transformations.

Old Russian princes in the works of the XVIII century. were called monarchs and constantly discussed on the topics of monarchy power, duty to the fatherland and subjects, honor and freedom, relevant to the New Age, but having little in common with the ideological world of the Middle Ages. The appearance of the Russian rulers (especially Peter the Great) sometimes became the prototype for the artistic images of their predecessors.

Knights and heroes

The first manifestations of the influence of the images of the Western European Middle Ages on the formation of ideas about the past in Russian culture should not be associated with historiography, but with art. In the XVIII century. another literary genre is being formed, associated with a peculiar image of Russian antiquity – these are literary tales. Tales of M. I. Popov, M. D. Chulkov, V. A. Levshin narrated about Slavic and Russian heroes, but at the same time, from the point of view of their genre originality, they turned out to be close to an adventurous and chivalrous novel. They were filled with adventures and fights, love stories and magic. Their heroes – Slavic knights and princes – were presented as beautiful and brave knights.

That is what Ilya Muromets is called in the tale of N. M. Karamzin:

It is like May red: red

roses with lilies

bloom on his face.

He is like a tender myrtle:

thin, straight and dignified by himself.

His gaze is faster than the eagle

and lighter than the month.

Who is this knight? – Ilya Muromets.

Ilya’s oath is close to the vows of wandering knights: “I swear to always follow the heroic prescriptions and charters of virtue, to be the protector of innocence, the poor, orphaned and unhappy widows, and to punish evil tyrants and wizards who frighten people’s hearts with my sword!”