Chronological framework of the history of ancient Central Asia

The wider the study of the past of Central Asia is developed, the more clearly the prominent role of this region in the history of world culture becomes.

The achievements of scientists, writers, artists, architects of Central Asia of the Middle Ages have long been recognized, but only recently it became clear that the foundation on which this brilliant civilization arose was the local cultures of the era of antiquity. Parthia, Margiana, Khorezm, Sogd, Bactria, Chach, Fergana – the culture of all these ancient regions was practically not studied a few decades ago, but was perceived by many historians as a distant periphery of Iran (“external Iran”), devoid of cultural originality. The discovery of the original cultures of ancient Central Asia raised the question of their origins, and again the answer was given by archeology – the Central Asian civilization of the Bronze Age was discovered.

At present, the periodization of the historical development of ancient Central Asia can be represented as follows:

- end of III – border of II-I millennium BC – civilization of the Bronze Age;

- border of II-I millennium BC – the beginning of the early Iron Age and the formation of a local class (slave-owning) society and statehood;

- VI century. BC. – the conquest of a significant part of Central Asia by the Achaemenids;

- end of IV century BC. – the conquests of Alexander the Great and the beginning of the Hellenistic era, the end of which in different regions falls at different times (in Parthia – the middle of the 3rd century BC, in Bactria – 130s BC, etc.) ). The subsequent period was the time of the formation of local statehood and the flourishing of the culture of the peoples of Central Asia within the framework of the emerging major powers, primarily Parthia and the Kushan kingdom.

- In the IV-V centuries. AD a crisis unfolds, marking the end of the slave and the beginning of the feudal era in the history of Central Asia.

Geographical conditions of Central Asia in antiquity

The civilizations of Central Asia arise in various historical and geographical regions. The natural conditions here are characterized by significant contrasts. Desert-steppe landscapes, and first of all the Karakum and Kyzylkum deserts, coexist with fertile oases irrigated by the Amu Darya and Syr Darya, a number of their tributaries and less significant waterways. The alpine massifs of the Tien Shan and Pamirs are very peculiar. Under these conditions, in a different ecological situation, the formation of cultures took place, different in their appearance and methods of farming.

- The interaction of various cultures is one of the specific features of the ancient history of Central Asia.

- Another feature of the origin of local civilizations here is the early and close ties with the ancient centers of other civilizations of the East, primarily Asia Minor.

The oldest civilizations of Central Asia

Dzheitun culture

These two main distinctive features were clearly manifested already at the initial stages of the history of the tribes and peoples of Central Asia. In the VI millennium BC. in the southwest of Central Asia, on a narrow foothill plain between the Kopetdag ridge and the Karakum desert, the Dzheytun Neolithic culture developed. Dzheitun tribes led a sedentary lifestyle, cultivated wheat and barley, and raised small livestock. The agricultural and cattle-breeding economy provided an increase in prosperity and the development of culture. The settlements of the Jeytun tribes consisted of solid adobe houses. The center of such a village was a large house – a communal sanctuary with walls decorated with paintings. The best preserved painting is in Pessedzhik-Depe, where a hunting scene was depicted. A number of features in the construction business,

In the 5th-4th millennia BC. there is a further development of the Central Asian agricultural and pastoral communities. They master the smelting of copper, begin to breed cattle, and then camels. Small canals are drawn to irrigate the fields. This was the beginning of irrigated agriculture, which gives high yields.

Altyn-Depe culture

The process of economic and cultural development led to the formation of the first cities in the southwest of Central Asia and the formation of a proto-urban civilization. Its most studied monument is called Altyn-Depe (studies by V.M. Masson). For the civilization Altyn-Depe, dating from about 2300-1900. BC, some features inherent in the developed cultures of the ancient East are characteristic. Its centers were two urban-type settlements – Altyn-Depe and Namazga-Depe. These “cities” were surrounded by fortress walls made of mud bricks, and the gates leading into the built-up space were framed by powerful pylon towers.

The center of Altyn-Depe was a monumental cult complex with a four-stage tower. It included numerous vaults, the house of the chief priest and the tomb of the priestly community. During excavations in the tomb, a golden bull’s head was found with a turquoise insert on the forehead in the shape of a moon disc. The entire temple complex was dedicated to the god of the moon, who in Mesopotamian mythology is often represented as a fiery bull. Another line of cultural ties leads to the Indus Valley, to the cities and settlements of the Harappan civilization . At Altyn-Depe, among the things put in rich graves, and among the treasures of valuable objects walled up in the walls, Harappan ivory products were found. Harappan-type seals were also found there.

Based on the materials of excavations, three different social groups can be distinguished in the composition of the population of the cities of the Altyndepen civilization.

- Ordinary community members, artisans and farmers lived in multi-room houses, which consisted of cramped closets.

- The houses of the communal nobility are more respectable: necklaces made of semi-precious stones, silver and bronze rings and seals were found in the tombs of wealthy communes.

- Property and social differentiation is more noticeable in the example of the third group of the population — leaders and priests. Their large houses had the correct layout and covered an area of 80-100 sq. m.

In the tombs, located in the “nobility quarter”, were placed a variety of jewelry, including gold and silver. There were also found ivory products, obviously imported. It is possible that slave labor was already used in the economy of the nobility. It is possible that the latter own burials devoid of any objects and located near rich tombs.

Successors of the Altyn-Depe civilization in the Murghab delta

In the middle of the 2nd millennium BC. the suburban settlements of this ancient civilization of Central Asia are declining and the main centers are moving to the east. In the delta of the river. Murghab, along the middle course of the Amu Darya, new oases of settled farmers are being formed. A number of fortified settlements of ancient communities have been excavated along the middle course of the Amu Darya, but large settlements have not yet been discovered. The settlements are fortified by walls with towers, and military weapons made of bronze are widely distributed. This may indicate constant wars. Many cultural features make it possible to conventionally consider the inhabitants of these oases to be direct descendants of the creators of the Altyn-Depe civilization, but at the same time, their culture has a number of new, fundamentally different phenomena.

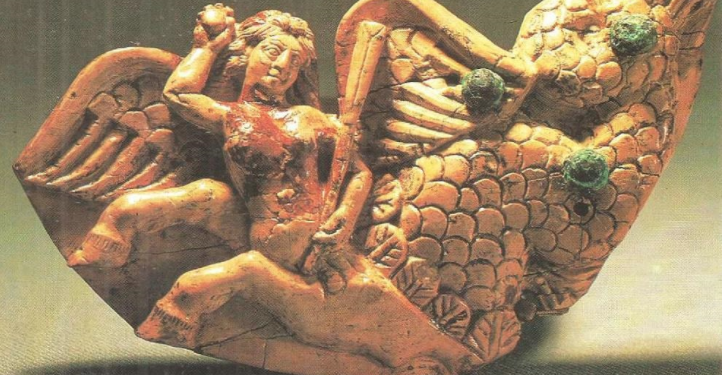

Such, in particular, are the flat stone seals, which depict dramatic scenes of the struggle of bulls and dragons, snakes attacking a tiger, and a mythological hero defeating wild beasts with extraordinary skill. Some of the images captured on them testify to the strengthening of ties with Mesopotamia and Elam, whose cultural impact is constantly increasing. By the beginning of the 1st millennium BC. the south of Central Asia was a zone of highly developed cultures of the ancient Eastern type.

Simultaneously with the creation of new oases in the south of Central Asia, tribes of steppe pastoralists settled in the northern regions. In the peculiar conditions of interaction of the steppe inhabitants of the north and the sedentary farmers of the south, the process of development of class relations and the formation of the state in Central Asia proceeded intensively. Technological progress at this time was associated primarily with the spread of iron. In the X-VII centuries. BC. iron products appear in the south of Central Asia, and from the VI-IV centuries. BC. iron is widely used for the manufacture of tools already throughout its territory. Complex irrigation systems are being created in the southeastern Caspian region and in the Murghab delta. The consequence of this is the gradual complication of the social structure of society, finding its expression in the creation of an oasis settlement system (which implies the existence of a clear system of management of the labor efforts of society within the oasis), as well as the emergence of various types of settlements. In particular, the centers of the oases were large settlements with citadels located on powerful platforms built of mud bricks. The citadels housed the monumental palaces of the rulers. Such, for example, is the Yaz-Depe settlement excavated by archaeologists in the Murghab delta, in ancient Margiana.

A culture of a similar type was spread on the territory of Bactria and, as shown by the latest archaeological research, also in the valleys of Zeravshan and Kashkadarya, that is, on the territory of the country, which in ancient times was called Sogd.

Central Asia as part of the Achaemenid state

When Central Asia partially became part of the Achaemenid state, the Achaemenids faced fierce opposition from a powerful alliance of nomadic tribes, which in ancient sources are called Massagets.

Ultimately, the main habitats of the nomads remained independent, but the main sedentary oases became part of the Achaemenid state and were combined into several satrapies. The Bactrian satrapy, probably as one of the most important, was often headed by a member of the ruling Achaemenid dynasty. The satrapies paid taxes to the central government and supplied military contingents, and the local aristocracy became an intermediary in such events. This contributed to the strengthening of social differentiation and the growth of class contradictions. So, during the accession to the throne of Darius I in 522 BC. uprisings and separatist movements swept the state, including Central Asia. The clashes in Margiana were especially fierce.

King Darius in the Behistun inscription says: “The country of Margiana became rebellious. One man named Frada, a Margian, they made (their) leader. After that, I sent (a messenger) to a Persian named Dadarshish, my servant, a satrap in Bactria, (and) I said to him this way: “Go, defeat the army that does not call itself mine.” Then Dadarshish went with an army and gave battle to the Margians . “

The decisive battle took place on December 10, 522 BC. In it the Margians were defeated. In the battle, 55,243 people were killed and 6972 of the rebels were taken prisoner. The report on the number of dead and prisoners clearly shows that the uprising in Margiana was indeed popular.

Since the V century. BC. a period of relative calm ensued. Cities develop, from which Marakanda becomes a major center, the capital of Sogd, located in the Zeravshan valley (on the site of modern Samarkand). Crafts achieved significant development, and regular international trade was being established. One of the most popular was the route through Bactria to India. Although local traits remain basic, the strengthening of ties with other countries leads to the emergence of foreign traditions. Following the canons of the imperial capital – Persepolis, local rulers build monumental palace buildings. Such a palace, for example, was discovered at the Kalalygyr settlement in Khorezm. The building was almost completely completed (obviously, at the turn of the 5th-4th centuries BC), but it did not settle down, as the political situation changed. Khorezm achieved independence, and the residence,

The conquest of Central Asia by Alexander the Great

The weakening Achaemenid empire suffered a crushing defeat from the army of Alexander the Great, however, the successful commander had to defend his conquests by force, and perhaps the greatest difficulties he encountered were in Central Asia. The last Achaemenid satrap of Bactria – Bessus – hastened to declare himself “the king of Asia” and tried to create a new state on the basis of the eastern satrapies. However, when the Greco-Macedonian troops approached, Bess fled and was soon handed over to Alexander by his own associates. The Greco-Macedonians met with serious resistance in Sogd, where the uprisings of the masses under the leadership of the energetic representative of the Sogdian nobility Spitamen shook the country for almost three years (329-327 BC). Alexander the Great suppressed this popular movement with brutal methods. According to sources, 70 thousand Sogdians were killed.

Alexander included the Sogdian and Bactrian contingents in his army, and his marriage to Roxane, the daughter of the noble Bactrian Oxyartes, was as romantic as it was political. Much attention was paid to urban planning – in Bactria, Sughd and Parthia (the region of modern southern Turkmenistan and northeastern Iran), cities were founded, which received the name of Alexandria.

Seleucid rule

Under Antiochus, a silver coin was minted in Bactria. Central Asia has entered a period of relative stabilization. However, as under the Achaemenids and Alexander the Great, political power was alien to most of the local population. The trend towards political independence has intensified further with the rise of the local economy. And the Seleucids considered the eastern satrapies only as a source of obtaining new forces and means for the wars they were waging in the west. The combination of various interests and aspirations led to the creation of independent states in Central Asia. Around 250 BC Bactrian satrap Diodotus declared himself an independent ruler. Almost simultaneously, Parthia fell away from the Seleucids.After the death of Alexander the Great, Central Asia became part of one of the states that had developed on the ruins of a new empire that did not manage to get stronger. This was the Seleucid state, which was about 305 BC. extended its power to Bactria. The early Seleucid kings viewed the eastern part of their power as a very important region, sought to raise its economic potential and strengthen their control over it. The son and heir of the founder of the Seleucus state – Antiochus, had to carry out this policy. In 292 BC. he was appointed co-ruler of his father with the transfer of the satrapies to him, lying to the east of the Euphrates. Bactra (Balkh) became the capital of his governorship. Antiochus energetically set about restoring the economy. In Margiana, he rebuilt the capital of the region, which received the name Antioch of Margiana,

Greco-Bactrian kingdom

Greco-Bactria occupied a special place among the independent Central Asian states . The typical Hellenistic structure of society was preserved here – power belonged to the conquerors: Greeks and Macedonians. Until recently, there were almost no archaeological materials that would make it possible to judge the culture of this peculiar state formation. However, in 1964, a large Greco-Bactrian city was discovered – the settlement of Ai-Khanum (on the territory of modern Afghanistan), the materials of which made it possible to get a clear idea of many features of the Greco-Bactrian culture.

Interesting monuments of the Greco-Bactrian culture were found in Tajikistan. First of all, this is the Saxonohur settlement. In its center was a large palace complex, a kind of miniature copy of the palace in Ai-Khanum. Finds made at the Takhti-Sangin settlement (Stone settlement) are even more convincing. A temple built according to the canons of “Iranian” sacred architecture was revealed here: a square cella surrounded by corridors, in a cella there are four columns. A significant number of magnificent works of art were found – believers brought them to the temple as donations. Among them are ceremonial weapons and statues; the first is in most cases of a purely Greek character, with reliefs of exceptional beauty. A small altar with a bronze figurine of Silenus Marsyas and a Greek inscription on it – a dedication to the god of the Oka River – was found here.

Based on all available sources, it can be argued that in the 80s. II century. BC. the Greeks of Bactria began to move south – crossed the Hindu Kush and undertook the conquest of the regions of India. But at the same time, another political event took place, which had important consequences – the military leader Eucratides rebelled against the legitimate kings of the Euthydemus dynasty. In the interaction of these tendencies – the gradual expansion of the possessions of the Greco-Bactrians on the Indo-Pakistani subcontinent and the constant fragmentation of the once unified state into separate small possessions – the entire further history of Greco-Bactria unfolds.

Parthian state

In the middle of the II century. BC. Central Asia has experienced serious events. The movement of nomadic tribes led to the death of Greco-Bactria and almost destroyed Parthia. In a difficult struggle with the nomads, two Parthian kings fell, and only under Mithridates II (123-87 BC) this threat was localized, and the invading tribes were given the province of Sakastan (modern Sistan) for settlement. Having got involved in a protracted confrontation with Rome, Parthia often suffered military and political defeats in the struggle against an experienced and strong rival, who also claimed the supremacy in Asia Minor.the Greco-Bactrian kingdom, the history of Parthia took a different path. Initially, the independence of Parthia from the Seleucids was proclaimed, as it was in Bactria, by a local satrap named Andragor. But soon the country was captured by tribes roaming nearby, whose leader Arshak in 247 BC. took the royal title. By the name of the founder of the dynasty, subsequent rulers of Parthia adopted the name Arshak as their throne name. Initially, the new state was relatively small and united, in addition to Parthia proper, neighboring Hyrcania, an area in the southeast of the Caspian. But already under Mithridates I (171-138 BC), active expansion to the west began up to Mesopotamia. Parthia becomes a world power. The ancient metropolis, now located in the northeast of the Parthian empire,

From the end of the 1st – the beginning of the 2nd century. AD there is a weakening of the Parthian state, accompanied by an increase in the independence of individual provinces, headed by members of the Arshakid clan or representatives of other noble Parthian families. Hyrcania, striving for independence, sends his ambassadors directly to Rome; a special dynasty was established in Margiana, the first representative of which, named Sanabar, refers to himself on coins with the same title as the ruling Arshakid – “king of kings”. Perhaps the power of the Margian ruler extended to the territory of Parthia proper, or Parthiena. In the 20s. Arshakid Parthia completely loses its independence under the blows of the founder of a new powerful dynasty Artashir Sassanid.

.

Economy and social structure of Parthia

For a number of regions of Central Asia, the Parthian period was a time of intensive development of urban life, the rise of handicraft industries and the expansion of the sphere of monetary circulation. In Parthien itself, the most famous city was Nisa, the ruins of which are located near present-day Ashgabat. The royal residence and the tomb of the elder Arshakids were located near the city proper. Long-term excavations by Soviet archaeologists have revealed remarkable architectural monuments, sculptures and, as already noted, the Parthian archive – well-known Soviet orientalists V.A.Livshits and I.M.Dyakonov are studying it. About 2 thousand documents of primary economic reporting of the tsarist economy were discovered. Thanks to the documents found, new data were obtained on the administrative structure of the Parthian kingdom, on the taxation system and land use. The analysis of numerous names and the calendar system is of great interest. One of the shards is a “memorandum” about the accession to the throne of the king. The study of these documents made it possible to restore the “family tree” of the first Arshakids.

The social structure of Parthia was decisively influenced by its conquest by the nomadic pair. The nomads made the local sedentary population dependent, which, according to ancient evidence, was “between slavery and freedom.” The peasants of Parthia, united in communities, were attached to the land, the cultivation of which was considered by them as a state obligation. They had to pay significant taxes. Slave labor played an important role in the economy. The existing management system required a clear work of the administrative and fiscal apparatus, as evidenced, in particular, by the Nissian economic documents. They carefully recorded income in kind from communal lands, temples and state farms.

Culture of Parthia

Parthian culture is a peculiar phenomenon. The synthesis of local and Greek principles is manifested in it much more strongly than in the culture of Greco-Bactria. The excavations carried out in the sacred center of Parthia, at the Old Nisa settlement (it was called Mithridatokert, which means “built by Mithridates”), clearly highlighted this feature of the Parthian culture. The buildings erected here typologically reflect either Iranian or even more ancient traditions. A typical example is the so-called square hall, which is a typical Iranian “temple of fire” in structure.

The Round Temple dates back to very ancient concepts of funerary architecture. This building has a peculiar layout, which is a combination of a circle with a square: the interior is round in plan, while the outer plan is square. However, all the buildings of Old Nisa bear clear signs of the influence of Hellenic architecture. Elements of the Greek order are constantly present in their decor, although they are not used the way it was done in the Greek world, but only to revive the interior. A particularly interesting new feature in the architecture of Parthia is the desire for the vertical development of the interior, the division of the interior space of the building into a number of tiers.

The sculpture of Mithridatokert amazes with its diversity. Small marble statues were found here, brought from the Mediterranean, most likely from Alexandria. Particularly famous is the statue depicting Aphrodite (the so-called Rodogun), an example of early Hellenistic sculpture, as well as a majestic statue of a woman, made in an archaic manner. Along with marble sculptures in Old Nisa, fragments of clay were also found. Some of them are presented in the generalized manner that is characteristic of the Central Asian school of the first centuries of our era, some were created under Greek influence, and possibly even by the Greeks themselves.