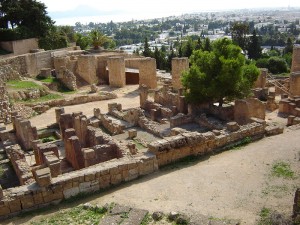

Founding of ancient Carthage

Ancient Carthage was founded in 814 BC. colonists from the Phoenician city of Fez. According to an ancient legend, Carthage was founded by the queen Elissa (Dido), who was forced to flee from Fez after her brother Pygmalion, the king of Tire, killed her husband Sychei in order to take possession of his wealth.

Its name in Phoenician “Kart-Hadasht” means in translation “New city”, perhaps, in contrast to the more ancient colony of Utica.

According to another legend about the founding of the city, Elissa was allowed to occupy as much land as a bull’s hide would cover. She acted quite cunningly – taking possession of a large piece of land, cutting the skin into narrow belts. Therefore, the citadel erected in this place began to be called Birsa (which means “skin”).

Carthage was originally a small city, not much different from other Phoenician colonies on the shores of the Mediterranean Sea, except for the significant fact that it was not part of the Tyrian state, although it retained spiritual ties with the metropolis.

The city’s economy was based primarily on intermediary trade. The craft was underdeveloped and did not differ from the oriental in its main technical and aesthetic characteristics. There was no agriculture. The Carthaginians did not have possessions behind the narrow space of the city itself, and for the land on which the city stood, they had to pay tribute to the local population. The political system of Carthage was originally a monarchy, and the head of state was the founder of the city. With her death, probably the only member of the royal family who was in Carthage disappeared. As a result, a republic was established in Carthage, and power passed to those ten “princeps” who had previously surrounded the queen.

Territorial expansion of Carthage

In the first half of the 7th century. BC. begins a new stage in the history of Carthage. It is possible that many new settlers from the metropolis moved there due to fear of the Assyrian invasion, and this led to the expansion of the city, attested by archeology. This strengthened it and allowed it to move to a more active trade – in particular, Carthage is replacing Phenicia itself in trade with Etruria. All this leads to significant changes in Carthage, the external expression of which is a change in the forms of ceramics, the revival of old Canaanite traditions already left in the East, the emergence of new, original forms of art and craft products.

Already at the beginning of the second stage of its history, Carthage becomes such a significant city that it can begin its own colonization. The first colony was bred by the Carthaginians around the middle of the 7th century. BC. on the island of Ebes off the east coast of Spain. Apparently, the Carthaginians did not want to oppose the interests of the metropolis in southern Spain and were looking for workarounds to Spanish silver and tin. However, Carthaginian activity in this area soon stumbled upon the rivalry of the Greeks, who settled in the early 6th century. BC. in southern Gaul and eastern Spain. The first round of the Carthaginian-Greek wars remained with the Greeks, who, although they did not oust the Carthaginians from Ebes, managed to paralyze this important point.

A setback in the extreme west of the Mediterranean forced the Carthaginians to turn to its center. They established a number of colonies east and west of their city and subdued the old Phoenician colonies in Africa. Having strengthened, the Carthaginians could no longer tolerate the situation that they paid tribute to the Libyans for their own territory. An attempt to free himself from tribute is associated with the name of the commander Malchus, who, having won victories in Africa, freed Carthage from tribute.

Somewhat later, in the 60-50s of the 6th century. BC, the same Malchus fought in Sicily, which apparently resulted in the subjugation of the Phoenician colonies on the island. And after victories in Sicily, Malchus crossed over to Sardinia but was defeated there. This defeat was for the Carthaginian oligarchs, who were afraid of the too victorious commander, an excuse to sentence him to exile. In response, Malchus returned to Carthage and seized power. However, he was soon defeated and executed. The leading place in the state was taken by Magon.

Magon and his successors faced difficult challenges. To the west of Italy, the Greeks established themselves, threatening the interests of both the Carthaginians and some Etruscan cities. With one of these cities – Caere, Carthage was in especially close economic and cultural contacts. In the middle of the 5th century. BC. the Carthaginians and Tseretans entered into an alliance directed against the Greeks who settled in Corsica. Around 535 BC at the Battle of Alalia, the Greeks defeated the combined Carthaginian-Ceretanian fleet, but suffered such heavy losses that they were forced to leave Corsica. The Battle of Alalia contributed to a clearer distribution of spheres of influence in the center of the Mediterranean. Sardinia was included in the Carthaginian sphere, which was confirmed by the Treaty of Carthage with Rome in 509 BC. However, the Carthaginians could not completely capture Sardinia.

The Carthaginians, led by rulers and generals from the Magonid family, fought a stubborn struggle on all fronts: in Africa, Spain and Sicily. In Africa, they subdued all the Phoenician colonies that were there, including the ancient Utica, which did not want to become part of their power for a long time, fought a war with the Greek colony of Cyrene, located between Carthage and Egypt, repulsed the attempt of the Spartan prince Dorieus to establish himself east of Carthage and drove the Greeks out of the arisen there were their cities west of the capital. They launched an offensive against the local tribes. In a bitter struggle, the Magonids managed to subdue them. Part of the conquered territory was directly subordinated to Carthage, forming its agricultural territory – the chora. The other part was left to the Libyans, but subject to the strict control of the Carthaginians, and the Libyans had to pay heavy taxes to their masters and serve in their army. The heavy Carthaginian yoke more than once caused powerful uprisings of the Libyans.

In Spain at the end of the VI century. BC. The Carthaginians took advantage of the Tartessian attack on Hades in order to intervene in the affairs of the Iberian Peninsula under the pretext of defending a consanguineous city. They captured Hades, who did not want to peacefully submit to his “savior”, which was followed by the collapse of the Tartessian state. Carthaginians at the beginning of the 5th century BC. established control over its remains. However, an attempt to extend it to Southeast Spain provoked strong resistance from the Greeks. In the naval battle of Artemisia, the Carthaginians were defeated and were forced to abandon their attempt. But the strait at the Pillars of Hercules remained under their rule.

At the end of the 6th – beginning of the 5th century. BC. Sicily became the scene of a fierce Carthaginian-Greek battle. Failed in Africa, Doria planned to establish himself in the west of Sicily, but was defeated by the Carthaginians and killed.

His death became a pretext for the Syracuse tyrant Gelon to war with Carthage. In 480 BC. The Carthaginians, having entered into an alliance with Xerxes, who was advancing at that time on Balkan Greece, and taking advantage of the difficult political situation in Sicily, where part of the Greek cities opposed Syracuse and entered into an alliance with Carthage, launched an attack on the Greek part of the island. But in the fierce battle at Gimer they were utterly defeated, and their commander Hamilcar, the son of Magon, perished. As a result, the Carthaginians could hardly stay in the previously captured small part of Sicily.

The Magonids made attempts to establish themselves on the Atlantic shores of Africa and Europe. To this end, in the first half of the 5th century. BC. two expeditions were undertaken:

- southward under the leadership of Gannon,

- in the north, led by Gimilkon.

So in the middle of the 5th century. BC. formed the Carthaginian state, which at that time became the largest and one of the strongest states in the Western Mediterranean. It consisted of –

- the northern coast of Africa west of the Greek Cyrenaica and several inland areas of this continent, as well as a small part of the Atlantic coast immediately south of the Pillars of Hercules;

- southwestern Spain and much of the Balearic Islands off the eastern coast of that country;

- Sardinia (in fact, only a part of it);

- Phoenician cities in the west of Sicily;

- islands between Sicily and Africa.

The internal situation of the Carthaginian state

The position of the cities, allies and subjects of Carthage

This power was a complex phenomenon. Its core was Carthage itself with a directly subordinate territory to it – the chora. The chora was located directly outside the city walls and was divided into separate territorial districts, governed by a special official, each district had several communities.

With the expansion of the Carthaginian state, the chorus sometimes included non-African possessions, like the part of Sardinia captured by the Carthaginians. Another component of the state was the Carthaginian colonies, which supervised the surrounding lands, were in some cases centers of trade and crafts, served as a reservoir for absorbing the “surplus” of the population. They had certain rights, but were under the control of a special resident sent from the capital.

The state included the old colonies of Tire. Some of them (Hades, Utica, Kossura) were officially considered equal with the capital, others legally occupied a lower position. But the official position and the real role in the power of these cities did not always coincide. So, Utica was practically in complete submission to Carthage (which later led more than once to the fact that this city, under favorable conditions for it, occupied an anti-Carfagenian position), and the legally lower cities of Sicily, in whose loyalty the Carthaginians were especially interested, enjoyed significant privileges.

В состав державы входили племена и города, находившиеся в подданстве у Карфагена. Это были ливийцы вне хоры и подчиненные племена Сардинии и Испании. Они тоже находились в разном положении. В их внутренние дела карфагеняне без нужды не вмешивались, ограничиваясь взятием заложников, привлечением к военной службе и довольно тяжелым налогом.

The Carthaginians also ruled over the “allies”. Those ruled independently, but were deprived of foreign policy initiative and had to supply contingents to the Carthaginian army. Their attempt to evade submission to the Carthaginians was seen as a rebellion. Some of them were also subject to tax, their loyalty was ensured by the hostages. But the farther from the borders of the state, the more independent the local kings, dynasts and tribes became. All this complex conglomerate of cities, peoples and tribes was overlaid with a grid of territorial division.

Economy and social structure

The creation of the power led to significant changes in the economic and social structure of Carthage. With the advent of land holdings, where the estates of aristocrats were located, a variety of agriculture began to develop in Carthage. It provided even more products to the Carthaginian merchants (however, often merchants themselves were rich landowners), and this stimulated the further growth of Carthaginian trade. Carthage becomes one of the largest trade centers in the Mediterranean.

A large number of subordinate population appears, located at different levels of the social ladder. At the very top of this ladder stood the Carthaginian slave-owning aristocracy, which constituted the top of the Carthaginian citizenship – “the people of Carthage”, and at the very bottom – slaves and groups of the dependent population close to them. Between these extremes, there was a whole range of foreigners, “meteks”, the so-called “Sidonian husbands” and other categories of the unequal, semi-dependent and dependent population, including residents of subordinate territories.

There was an opposition to the granting of Carthaginian citizenship to the rest of the population of the state, including the slaves. The civilian collective itself consisted of two groups –

- aristocrats, or “powerful”, and

- “Small”, i.e. plebs.

Despite being divided into two groups, the citizens acted together as a close-knit natural association of oppressors, interested in exploiting all other inhabitants of the power.

The system of property and power in Carthage

The material basis of the civilian collective was communal property, which acted in two forms: the property of the entire community (for example, the arsenal, shipyards, etc.) and the property of individual citizens (land, workshops, shops, ships, except for the state, especially the military, etc.). etc.). Apart from the communal property, there was no other sector. Even the property of the temples was brought under the control of the community.

The civic collective, in theory, also possessed the entirety of state power. We do not know exactly what posts were held by Malchus who seized power and the Magonids who came after him to rule the state (sources in this regard are very contradictory). In fact, their position seemed to resemble that of the Greek tyrants. Under the leadership of the Magonids, the Carthaginian state was actually created. But then it seemed to the Carthaginian aristocrats that this family became “difficult for the freedom of the state,” and Magon’s grandchildren were expelled. The expulsion of the Magonids in the middle of the 5th century. BC. led to the approval of the republican form of government.

The highest power in the republic, at least officially, and in critical moments and in fact, belonged to the people’s assembly, which embodied the sovereign will of the civilian collective. In fact, the leadership was carried out by oligarchic councils and magistrates elected from among the rich and noble citizens, primarily two Sufets, in whose hands the executive power was held for a year.

The people could intervene in government affairs only in case of disagreements among the rulers, which arose during periods of political crises. The people also had the right to choose, albeit very limited, of advisers and magistrates. In addition, the “people of Carthage” were tamed in every possible way by the aristocrats, who gave them a share of the benefits of the existence of the power: not only the “powerful”, but also the “small” profited from the sea and commercial power of Carthage, from the “plebs” were recruited people sent for supervision over subordinate communities and tribes, participation in wars gave a certain benefit, because in the presence of a significant mercenary army, citizens were still not completely separated from military service, they were represented at various levels of the land army, from privates to the commander, and especially in the navy.

Thus, in Carthage, a self-sufficient civic collective was formed, possessing sovereign power and based on communal property, next to which there was no royal power over citizenship, nor a non-communal sector in the socio-economic sense. Therefore, we can say that a policy arose here, i.e. such a form of economic, social and political organization of citizens, which is characteristic of the ancient version of the ancient society. Comparing the situation in Carthage with the situation in the metropolis, it should be noted that the cities of Phenicia itself, with all the development of the commodity economy, remained within the framework of the eastern version of the development of the ancient society, and Carthage became an ancient state.

The formation of the Carthaginian polis and the formation of the state were the main content of the second stage of the history of Carthage. The Carthaginian state arose during the fierce struggle of the Carthaginians with both the local population and the Greeks. Wars with the latter were of a pronounced imperialist character, for they were fought for the seizure and exploitation of foreign territories and peoples.

Rise of Carthage

From the second half of the 5th century. BC. the third stage of the Carthaginian history begins. The state had already been created, and now it was about its expansion and attempts to establish hegemony in the Western Mediterranean. The main obstacle to this was originally all the same Western Greeks. In 409 BC. The Carthaginian general Hannibal landed in Motia, and a new round of wars began in Sicily, which continued with interruptions for more than a century and a half.

Initially, success leaned towards Carthage. The Carthaginians subdued the Elim and Sicans living in the west of Sicily and launched an offensive against Syracuse, the most powerful Greek city on the island and the most implacable enemy of Carthage. In 406 the Carthaginians laid siege to Syracuse, and the plague that had just begun in the Carthaginian camp saved the Syracusans. World 405 BC secured the western part of Sicily for Carthage. True, this success turned out to be fragile, and the border between Carthaginian and Greek Sicily always remained pulsating, moving either to the east or to the west as one or another side succeeded.

The failures of the Carthaginian army almost immediately responded with an exacerbation of internal contradictions in Carthage, including powerful uprisings of the Libyans and slaves. End of V – first half of IV century BC. were a time of sharp clashes within citizenship, both between individual groups of aristocrats, and, apparently, between the “plebs” involved in these clashes and aristocratic groups. At the same time, the slaves rose up against the masters, and the subordinate peoples against the Carthaginians. And only with calmness within the state, the Carthaginian government was able in the middle of the 4th century. BC. resume external expansion.

Then the Carthaginians established control over the southeast of Spain, which they unsuccessfully tried to do a century and a half ago. In Sicily, they launched a new offensive against the Greeks and achieved a number of successes, again being under the walls of Syracuse and even capturing their port. The Syracusans were forced to turn to their metropolis Corinth for help, and from there an army arrived led by a capable commander Timoleont. The commander of the Carthaginian troops in Sicily, Gannon, was unable to prevent the landing of Timoleont and was recalled to Africa, and his successor was defeated and cleared the Syracuse harbor. Gannon, returning to Carthage, decided to use the resulting situation and seize power. After the failure of the coup, he fled the city, armed 20 thousand slaves and called on the Libyans and Moors to arms. The rebellion was defeated

However, soon a turn of affairs in Sicily forced the Carthaginian government to turn to Gisgon. The Carthaginians were severely defeated by Timoleon, and then a new army was sent there, led by Gisgon. Gisgon entered into an alliance with some of the tyrants of the Greek cities of the island and defeated individual units of Timoleon’s army. This allowed in 339 BC. conclude a relatively advantageous peace for Carthage, according to which he retained his possessions in Sicily. After these events, the Gannonian family for a long time became the most influential in Carthage, although there could be no question of any tyranny, as was the case with the Magonids.

The wars with the Syracuse Greeks went on as usual and with varying success. At the end of the IV century. BC. the Greeks even landed in Africa, threatening Carthage directly. The Carthaginian general Bomilcar decided to seize the opportunity and seize power. But the citizens opposed him, suppressing the rebellion. And soon the Greeks were repulsed from the Carthaginian walls and returned to Sicily. The attempt of the Epirus king Pyrrhus to oust the Carthaginians from Sicily in the 70s was also unsuccessful. III century. BC. All these endless and exhausting wars showed that neither the Carthaginians nor the Greeks had the strength to take Sicily from each other.

The emergence of a new rival – Rome

The situation changed in the 60s. III century. BC, when a new predator, Rome, intervened in this struggle. In 264, the first war broke out between Carthage and Rome. In 241 it ended with the complete loss of Sicily.

This outcome of the war aggravated the contradictions in Carthage and gave rise to an acute internal crisis there. Its most striking manifestation was a powerful uprising, in which hired soldiers took part, dissatisfied with the failure to pay the money due to them, the local population, who sought to throw off the heavy Carthaginian oppression, slaves who hated their masters. The uprising unfolded in the immediate vicinity of Carthage, probably also encompassing Sardinia and Spain. The fate of Carthage hung in the balance. With great difficulty and at the cost of incredible cruelty, Hamilcar, who had previously become famous in Sicily, managed to suppress this uprising, and then went to Spain, continuing to “pacify” the Carthaginian possessions. With Sardinia, they had to say goodbye, yielding it to Rome, which was threatening a new war.

The second aspect of the crisis was the growing role of citizenship. The rank-and-file, who in theory had sovereign power, now sought to turn theory into practice. A democratic “party” emerged, headed by Hasdrubal. A split also occurred among the oligarchy, in which two groups emerged.

- One was headed by Gannon from the influential Gannonid family – they stood for a cautious and peaceful policy that excluded a new conflict with Rome;

- and the other – Hamilcar, representing the Barkid family (nicknamed Hamilcar – Barca, literally, “lightning”) – they were for an active one, with the goal of taking revenge from the Romans.

The rise of the Barkids and the war with Rome

Wide circles of citizenship were also interested in revenge, for which the inflow of wealth from the subordinate lands and from the monopoly of sea trade was beneficial. Therefore, an alliance arose between the Barkids and the Democrats, sealed by Hasdrubal’s marriage to Hamilcar’s daughter. Relying on the support of democracy, Hamilcar managed to overcome the intrigues of his enemies and go to Spain. In Spain, Hamilcar and his successors from the Barkid family, including his son-in-law Hasdrubal, greatly expanded the Carthaginian possessions.

Already Hamilcar considered Spain as a springboard for a new war with Rome. His son Hannibal in 218 BC. provoked this war. The Second Punic War began. Hannibal himself went to Italy, leaving his brother in Spain. Military operations unfolded on several fronts, and the Carthaginian generals (especially Hannibal) won a number of victories. But the victory in the war remained with Rome.

World 201 BC deprived Carthage of the military fleet, of all non-African possessions and forced the Carthaginians to recognize the independence of Numidia in Africa, to whose king the Carthaginians had to return all the possessions of his ancestors (this article put a “time bomb” under Carthage), and the Carthaginians themselves did not have the right to wage war without permission Rome. This war not only deprived Carthage of the position of a great power, but also significantly limited its sovereignty. The third stage of the Carthaginian history, which began with such happy omens, ended with the bankruptcy of the Carthaginian aristocracy, which had ruled the republic for so long.

Internal position

At this stage, no radical transformation of the economic, social and political life of Carthage took place. But certain changes did take place. In the IV century. BC. Carthage began to mint its own coin. A certain Hellenization of a part of the Carthaginian aristocracy takes place, and two cultures arise in Carthaginian society, as is typical for the Hellenistic world. As in the Hellenistic states, in a number of cases civil and military power is concentrated in the same hands. In Spain, a semi-independent state of the Barkids arises, the heads of which felt their kinship with the then rulers of the Middle East and where a system of relations between the conquerors and the local population appeared, similar to that existing in the Hellenistic states.

Carthage had significant tracts of land suitable for cultivation. In contrast to other Phoenician city-states in Carthage, large-scale agricultural plantations developed on a large scale, where the labor of numerous slaves was exploited. The plantation economy of Carthage played a very important role in the economic history of the ancient world, since it influenced the development of the same type of slave economy, first in Sicily, and then in Italy.

In the VI century. BC. or maybe in the 5th century. BC. in Carthage lived a theoretical writer of the plantation slave economy Magon, whose great work enjoyed such fame that the Roman army, which besieged Carthage in the middle of the II century. BC, the order was given to preserve this work. And he was really saved. By decree of the Roman Senate, Mago’s work was translated from the Phoenician language into Latin, and then was used by all theorists of agriculture in Rome. For their plantation economy, for their craft workshops and for their galleys, the Carthaginians needed a huge number of slaves, selected by them from among the prisoners of war and bought.

Sunset of Carthage

The defeat in the second war with Rome opened the last stage of Carthaginian history. Carthage lost its power, and its possessions were reduced to a small district near the city itself. Opportunities to exploit the non-Carthaginian population disappeared. Large groups of dependent and semi-dependent population got out of the control of the Carthaginian aristocracy. The agricultural area was sharply reduced, and trade again acquired predominant importance.

If earlier not only the nobility, but also the “plebs” received certain benefits from the existence of the state, now they have disappeared. This naturally caused an acute social and political crisis, which has now gone beyond the framework of existing institutions.

In 195 BC. Hannibal, becoming a Sufet, carried out a reform of the state system, which struck a blow to the very foundations of the previous system with its domination of the aristocracy and opened the way to practical power, on the one hand, for broad sections of the civilian population, and on the other, for demagogues who could take advantage of the movement of these strata. Under these conditions, a fierce political struggle unfolded in Carthage, reflecting sharp contradictions within the civilian collective. At first, the Carthaginian oligarchy managed to take revenge, with the help of the Romans forcing Hannibal to flee without completing the work begun. But the oligarchs were unable to keep their power intact.

By the middle of the II century. BC. in Carthage, three political groups fought. In the course of this struggle, Hasdrubal became the leading figure, who led the anti-Roman group, and his position led to the establishment of a regime such as the Greek minor tyranny. The rise of Hasdrubal frightened the Romans. In 149 BC. Rome started a third war with Carthage. This time, for the Carthaginians, it was no longer about domination over certain subjects and not about hegemony, but about their own life and death. The war was practically reduced to the siege of Carthage. Despite the heroic resistance of the citizens, in 146 BC. the city fell and was destroyed. Most of the citizens died in the war, and the rest were taken into slavery by the Romans. The history of Phoenician Carthage is over.

The history of Carthage shows the process of transformation of the eastern city into an ancient state, the formation of a polis. And having become a polis, Carthage also experienced a crisis of this form of organization of ancient society. At the same time, it must be emphasized that what could have been the way out of the crisis here, we do not know, since the natural course of events was interrupted by Rome, which dealt a fatal blow to Carthage. The Phoenician cities of the metropolis, which developed in different historical conditions, remained within the eastern version of the ancient world and, having become part of the Hellenistic states, already entered a new historical path within them.