A sling is probably the oldest and most widespread throwing weapon of ranged combat. A sling was in use until the era of firearms, and in some places, it continues to be used today. This throwing weapon appeared in ancient times and became very popular among the Greeks and Romans, who used it not only as a weapon but also as a way of communicating with the enemy, sending him certain wishes and recommendations along with the cores.

At the source

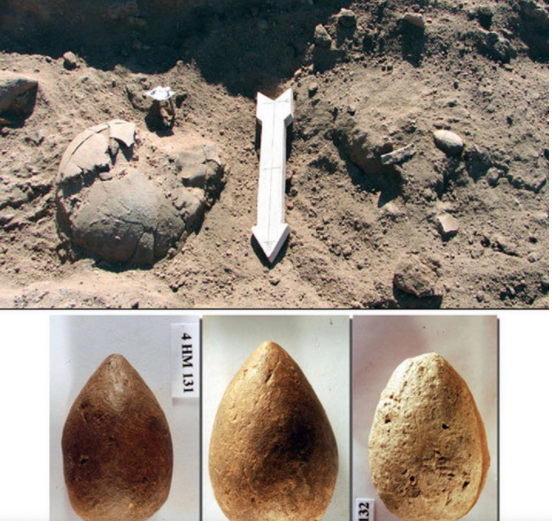

What is the secret of the sling? Firstly, it is extremely easy to manufacture, and secondly, it is very effective in practice. Hundreds of researchers find shells for sling already in the remnants of the Neolithic settlements of the Middle East. When excavating the site of Hamukar in Northeastern Syria, destroyed about 3,500 BC, archaeologists discovered about 1,100 clay cores. During the excavation of the Celtic site of Maiden Castle in Dorset, 22,000 pebble cores were found that were used by the locals to defend against the attack of the Romans in 43 C.E. Both finds have a clear military context.

Technically, a sling is a braided from plant fibers or horse hair (experts say horse hair is the best material) a belt with an extension in the middle in which a stone or core is inserted. The slinger tied one end of the belt to the thumb, and the other clamped between the thumb and forefinger. To prevent the core from slipping ahead of time, a knot could be made. After two or three strokes above his head, the man let go of the free end of the sling, and the projectile with great force flew right at the target.

A curious specimen of slings is kept at the Petrie Museum at University College London. It was found during excavations of El Lahuna in the Fayum oasis in Egypt and dates from about 800 BC. A sling of ten woven strands of linen thread was made. It is interesting that the weaving technique itself is identical to that used in the manufacture of slings in Peru in the 19th – 20th centuries. The length of the only surviving slings is 570 mm, the thickness is about 6 mm, the “hammock” for the core has dimensions 125 × 70 mm. The initial length of the weapon was probably 1270 mm.

Stone, clay and lead

The first sling shells were any handy stones of convenient shape and size. Gradually, experimentally, people established a relationship between the size, shape, weight of the projectile and its throwing range, energy and impact force. The shooters enjoyed the greatest preference for sea or river pebbles, the finds of which on the remains of settlements indicate that it was used as a weapon. Then clay kernels appeared, to which the masters gave a spherical, and later ellipsoidal shape. The advantage of clay cores was their standard size and weight, which allowed the shooter to save time on choosing the right projectile. The sling cores were usually made of pure clay and were quite heavy. Since they often burst during firing in an oven, they were usually simply dried in the sun. In classical Greece, kernels were also cast fromlead . Due to the high density of the material, such cores were almost twice as superior to stone and clay in terms of firing range and the severity of the strike when it hits the target. The Romans, because of the similarity in size, called the kernels for sling acorns (glandes).

Archaeological finds of lead cores have been known since at least the 5th century BC. They had an elongated biconical shape, a volume of 5 cm3 to 65 cm3 and a mass of 20 to 185 g (average 24–46 g). The most famous mass find is the 500 lead cores discovered in the 1930s during the excavation of Olynthus. This city in 348 BC besieged, stormed and destroyed the troops of the Macedonian king Philip II. The found cores belonged to both sides of the conflict. Approximately 100 shells had inscriptions by which today they can be identified. The mass of most finds ranged from 18 to 35 g with a significant predominance of a group weighing 24–27 g. Those that were identified as belonging to the defenders of the city, in nine cases out of fourteen weighed less than 27 g. Of the 23 Macedonian kernels, 16 had a mass between 30 and 35 g. One hypothesis is that the lighter nuclei were designed to use several copies at a time, which would create a fraction effect during mass shooting. The experiments confirmed the technical feasibility of such firing, but sources remain silent about it.

Lead kernels from Italy and Sicily differ little in size and weight from those found in Greece. A completely special group consists of shells that used Balearic slingers. Usually they served as mercenaries in the armies of the Carthaginians, and later among the Greeks and Romans. Diodorus of Sicily reports that the Balears threw stones weighing 1 minute, that is 330 g, using slings, “ besides with such force that it seemed as if the catapult was sending shells”. The information of Diodorus is confirmed by Caesar, who reported in “Notes” that the Balearic slingers who served in his army threw stone pounds weighing pounds (327 g) at the enemy. The diameter of such a core was 6.3 cm, that is, the shell had the size of a tennis ball. Interestingly, during the excavation of Carthage in 1905, archaeologists found in the arsenal of approximately 20,000 clay egg-shaped cores and varying degrees of firing measuring 6 × 4 cm and weighing from 105 to 124 g.

Studies of ballistic missile projectiles show that the strength and range of the throw depend mainly on air resistance. Due to the friction of the projectile on the air during flight, the initial acceleration energy is gradually consumed, the loss of which occurs the faster, the larger its surface area. The density of lead is many times greater than the density of clay and, to a large extent, the density of stone. With the same weight of 40 g, the lead core will have a significantly smaller surface area than stone or clay. Accordingly, it will experience less air resistance in flight, fly a greater distance, and at the same time retain more initial throw energy. All this even at the end allows him to strike a powerful blow and hit the enemy’s manpower when it hits the target.

Application efficiency

The above calculations confirm the practical observations of Xenophon, who in his Anabasis compared the effectiveness of lead and stone cores:

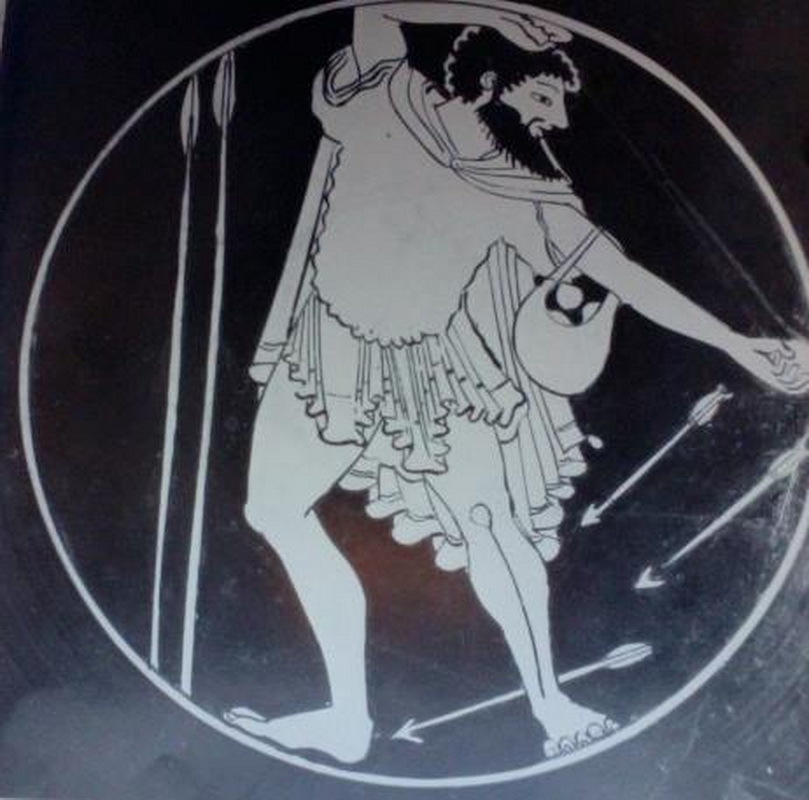

There are several methods for using slings. The technique of the ancient Greeks can be reconstructed on the basis of a large number of surviving images, as well as some narrative sources. Important information is provided by Virgil’s line, which describes how the Etruscan Mezentius “ having described with a sling of a whistle three times above himself, a lead ingot (…) sent”. Here, a technique is used in which a sling is untwisted in a horizontal plane around the head in a clockwise direction. A shot is fired when the sling with the core clamped in it is turned in the direction of the target. According to experts, this method allows you to make the most of the hand lever of the shooter and the capabilities of weapons. In addition, the sling can vary the elevation angle of the weapon’s rotation plane depending on the distance to the target: from a practically horizontal loop for a closely spaced target to a significant elevation angle for a long-range throw.

With a different sling technique, it spins in a vertical plane. When untwisted counterclockwise, the shot is fired when the projectile is at the highest point of lift. If the rotation occurs clockwise, the projectile is released at the bottom of the trajectory. Compared with the previous one, this method is less effective, since it neglects the lever arm of the sling and limits the length of the sling belt. During rotation, less energy is accumulated, which affects the strength of the shot and, accordingly, on the flight range.

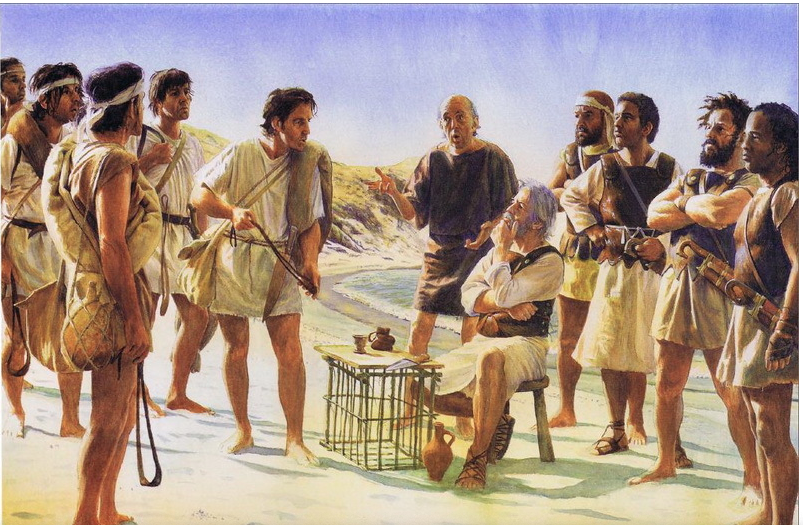

Slingers in the armies

Slingers made up a very significant part of the ancient armies. Syracuse tyrant Gelon in 480 BC He promised the Greeks to set up an army of 26,000 soldiers, of whom 2,000 were slingers, that is, one slinger each accounted for ten foot soldiers and two horsemen. Athenians in 415 BC sent 5,220 foot soldiers, 30 horsemen, 480 archers and 700 slingers to the Sicilian expedition. All of them were mercenaries, but of Greek origin. On the advice of Xenophon, 10,000 Greek mercenaries during the famous retreat to the sea after the Battle of Kunax formed a corps of 200 slingers and 200 Cretan archers. These arrows have proven effective in clashes with Persian lightly armed soldiers.

The most famous among the Greeks were the Rhodes slingers. Skilful sling arrows were also considered Lokra, Akarnan and Aetolians. Last Strabo even ascribes the invention of the sling. The Roman historian Titus Livius wrote about the skill of the Achaean slingers that they could get from any distance, not just in the head, but in any part of the face wherever they want.

In the western Mediterranean, Balearic slingers enjoyed high authority, throwing stones the size of a tennis ball over long distances and with amazing force. Diodorus of Sicily talks about their art and explains it with relentless training:

The Balears served as mercenaries in the Carthaginian army, where on the eve of the Second Punic War, there were 1,380 slingers per 26,000 foot soldiers and 1,200 horsemen. After the victory of Rome and the annexation of the Balearic Islands in 123 BC the balears continued to serve in the Roman army.

In the ancient period of its history, the Romans recruited slingers from among poor citizens, and later preferred to attract allies. More often than others, Balearic slingers appear in the sources, who participated in most Roman military campaigns of the 2nd – 1st centuries BC. Also mentioned are the Cretans, Achaeans, Aetolians and other Greeks, as well as Thracians, Syrians, Arabs and others. Unlike the republican period of Roman history, such references become rare for the army of imperial time. Nevertheless, the presence of these troops in the Roman army is confirmed by finds of lead cores, inscriptions and images, including on the reliefs of the Column of Trajan and the Column of Marcus Aurelius in Rome.