North African rock carvings

In addition to inventory and the remains of meals, primitive Africans left behind many rock paintings, which the locals call “inscribed stones” ( hajerat mektubat ). They are very numerous on the territory of North Africa; for 40 years they served as the object of research by G.B. Flaman. But since then, as in 1921, his classic work on the “Painted Stones” was published, science has been enriched by many new discoveries and published works. Problems of performance technique, themes and dating of rock paintings in various regions of the Sahara were studied by E.F. Gauthier, A. Breil, M. Reigas, T. Monodom; Libya – P. Graziosi and L. Frobenius; Eastern Berberia – M. Solignac; South Oran – R. Wofrey. Although the description and systematization of rock carvings is far from complete, we currently have a sufficient number of sources to consider them as a whole.

Based on the works of GB Flaman, there are three groups of images.

- Some, unmistakably embossed in flint, is characterized by wide and deep lines, uniform and shrouded in mystery. At first, the engravers applied the image with strokes, then they punctured a distinct dotted line with an awl, and only then, with the help of careful polishing with a stone tool, they obtained a continuous and clear line.

- On these images, other drawings are applied, of a much smaller size, executed with rough dotted lines and extremely schematic; usually, they are accompanied by Libyan-Berber letters or inscriptions and depict animals that are still found in Berberia (some animals, such as the camel, appeared here relatively recently).

- The third group includes very easily outlined drawings of modern execution, accompanied by Arabic inscriptions. Obviously, they were made after the 7th century AD.

Images of animals and people

The first most ancient group of images is the most controversial. To establish their age, we lack those elements that were used, for example, by A. Breuil in the classification of French and Spanish drawings of the Aurignaque, Madeleine and Solutre periods, which were in the cultural layers of these periods, among precisely dated remains of fauna and inventory. Images of animals in Berberia do not allow one to draw the same exact conclusions about the time to which these drawings refer, as, for example, in France, since the Maghreb fauna has undergone relatively little change. Finally, the inventory found in the vicinity of the rock carvings cannot serve as a serious basis for their dating, since they usually belong to different periods and often have nothing to do with the drawings.

However, in South Oran, the drawings invariably coexist with the remains of the Neolithic of the Capsian tradition (Capsian epoch 3000−1900 BC), “in the absence of tools from all other periods of the Upper Paleolithic, Mesolithic or Neolithic” (R. Wofrey). Perhaps further research will show that this coincidence is not accidental.

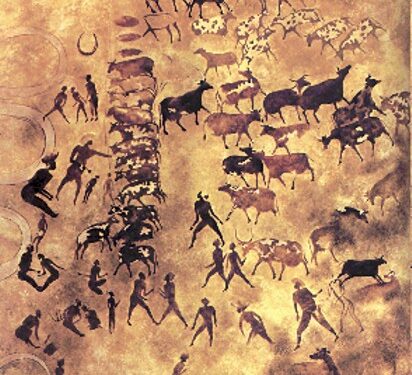

The most typical is the image of the late Pleistocene bubalus antiquus with huge horns. G.B. But the bubalus (buffalo) could, like an elephant, hold out until a later time. The depictions of elephants are very numerous, but there is debate whether we are dealing with the ancient elephas atlanticus or the modern elephas africanus, which lived in Africa from the Pleistocene to its complete destruction during the era of Roman civilization. The drawings also depict antelopes, lions, panthers, giraffes, ostriches, as well as domestic animals, especially rams with a round object on their head resembling the disk of the Ram Amon. Explain the origin of this emblem, which also appears in the images of cattle, it is not so simple, and it is still not established whether it should be considered a symbol of the sun. The question of the origin of the cult of the ram has also not yet been resolved. Some researchers identify him with the Theban god, and R. Wofrey speaks in this connection about a “derived cult”. Others believe that the ram depicted in the rock art of the Sahara “has nothing to do with the god Amun, who was not yet born” (G. Germain), and believe that the cultures of Egypt and the Maghreb had some common source.

In some pictures, animals are shown in groups. Of greatest interest is the battle scene of ancient buffaloes from Al Rish (south of Aflu) and the image of a wild boar pursued by lions and jackals found at Kef Misihuera ( mixed community of Oued Sherf).

Some images of people are of great historical and documentary significance. These people, judging by the drawings, undoubtedly wore phallic cases and clothes made of animal skins; some celebrated their leaders with a crown of feathers, undoubtedly the privilege of the nobility; others adorned themselves with necklaces and bracelets. They painted their bodies with ocher. A bow, arrow, boomerang and shield were used as weapons.

Among the rock carvings of a person, the most remarkable from a source study point of view is, of course, a drawing of a man from Ksar al-Ahmar (near Grenville in South Oran), waving an object in which it is easy to recognize an ax made of polished stone.

Dating of rock carvings

If no one disputes the fact that rock painting lasted many centuries after the onset of our era, then this unanimity disappears when trying to date, at least approximately, its first manifestations. In fact, researchers often complicated the problem they faced by passing off a working hypothesis as generally accepted conclusions. At present, the conclusions of GB Flaman, made by him on the basis of differences in the methods of making rock paintings and the thickness of the patina layer, are no longer recognized. The reliability of the dates established by comparing the rock paintings with dated archaeological sites depends, naturally, on the correctness of the dating of the latter. As for paleozoological drawings, their significance is often exaggerated, since it is impossible to prove that this or that drawing depicts, for example, the last buffalo or the first camel. In addition, what is connected with the camel, in particular its history, continues to remain so mysterious that researchers hesitate to attach decisive importance to its dating in rock carvings. The classification of Adrar-Akhnet’s drawings proposed by T. Monod into two periods – before the appearance of the camel and after – did not receive unanimous support. Only the image of a domestic horse in the drawings serves as an indisputable indication of the time of their origin – not earlier than the second half of the II millennium. Monodom’s classification of Adrar-Akhnet’s drawings into two periods – before and after the appearance of the camel – did not receive unanimous support. Only the image of a domestic horse in the drawings serves as an indisputable indication of the time of their origin – not earlier than the second half of the 2nd millennium. Monodom’s classification of Adrar-Akhnet’s drawings into two periods – before and after the appearance of the camel – did not receive unanimous support. Only the image of a domestic horse in the drawings serves as an indisputable indication of the time of their origin – not earlier than the second half of the II millennium.

In essence, the problem boils down to determining whether the earliest rock paintings predate the Neolithic or not. Naturalists M. Boulle, M. Solignac, L. Jolot and some researchers of the prehistoric period, in particular A. Kuhn, answer this question in the affirmative and date the primitive drawings to the Upper Paleolithic (Capsian period), and the Abbot A. Breuil, who is very inclined to identify shades, even ventured to introduce the term “epipaleolithic”. But most researchers, including G.B. Flaman, A. Obermeier and especially R. Wofrey, are convinced that rock art belongs to the Neolithic era. At the same time, however, they do not go to such an extreme as Art. Gzell, who at one time attributed it to a period of about 3 thousand years BC. e. Numerous arguments have been made for and against each of these claims.

As for the numerous comparisons of rock paintings of North Africa with images found in Spain and especially in South Africa, identifying similarities between North African paintings and some works of Aegean or Egyptian art, they lose their scientific significance as soon as they try to establish the origin by analogy. Maghreb drawings, until now, and perhaps forever, shrouded in mystery.

The prehistory of the Maghreb to some extent gives an idea of its history. To study them too often one has to be content with only an approximate chronology. If scientists are not able to come to accurate conclusions regarding primitive peoples, then no less difficult is the study of the historical people of the Berbers, although they, if not ethnically, then socially represent a living and stable reality.