General and special in the Hellenistic culture of different regions

The most important legacy of the Hellenistic world was a culture that was widespread on the periphery of the Hellenistic world and had a huge impact on the development of Roman culture (especially the eastern Roman provinces), as well as on the culture of other peoples of antiquity and the Middle Ages.

Hellenistic culture was not uniform; in each area it was formed as a result of the interaction of local stable traditional elements of culture with the culture brought by the conquerors and settlers, Greeks and non-Greeks. The combination of these elements, the forms of synthesis, were determined by the influence of many circumstances: the numerical ratio of various ethnic groups (local and newcomers), the level of their culture, social organization, economic conditions, political situation, and so on, – specific to a given area. Even when comparing the large Hellenistic cities – Alexandria, Antioch on Orontes, Pergamum, Pella, etc., where the Greco-Macedonian population played a leading role, features of cultural life that are specific to each city are clearly visible; the more clearly they appear in the inner regions of the Hellenistic states.

However, Hellenistic culture can be considered as an integral phenomenon: all of its local variants have some common features, due, on the one hand, to the obligatory participation in the synthesis of elements of Greek culture, on the other hand, to similar trends in the socio-economic and political development of society throughout the territory of the Hellenistic world. The development of cities, commodity-money relations, trade relations in the Mediterranean and Western Asia largely determined the formation of material and spiritual culture during the Hellenistic period. The formation of Hellenistic monarchies in combination with the polis structure contributed to the emergence of new legal relations, a new socio-psychological image of man, a new content of his ideology. In Hellenistic culture more prominently than in classical Greek,

Factors of the spread of Hellenistic culture

Education system

One of the stimuli for the formation of Hellenistic culture was the spread of the Hellenic way of life and the Hellenic education system. Gymnasiums with palestras, theaters, stadiums and hippodromes arose in the policies and in the eastern cities that received the status of the policy; even in small settlements that did not have a polis status, but were inhabited by clerukhs, artisans and other people from the Balkan Peninsula and the coast of Asia Minor, Greek teachers and gymnasiums appeared.

Much attention was paid to teaching young people, and, consequently, preserving the foundations of Hellenic culture in the original Greek cities. The educational system, as the authors of the Hellenistic time describe it, consisted of two or three stages, depending on the economic and cultural potential of the polis.

- Boys, starting from the age of 7, were taught by private teachers or in public schools in reading, writing, counting, drawing, gymnastics, acquainting them with the myths, poems of Homer and Hesiod: listening and memorizing these works, children learned the basics of the polis ethical and religious worldview. Further education of young people took place in gymnasiums;

- From the age of 12, adolescents were required to attend a palestra (physical training school) in order to master the art of pentathlon (pentathlon, which included running, jumping, wrestling, throwing a discus and javelin), and at the same time grammar school, where they studied the works of poets, historians and logographers, geometry , the beginning of astronomy, learned to play musical instruments;

- 15-17-year-olds listened to lectures on rhetoric, ethics, logic, philosophy, mathematics, astronomy, geography, learned horseback riding, fist fighting, the beginnings of military affairs;

- In the gymnasium, they continued their education and physical training of the ephebe – young men who had reached adulthood and were subject to conscription for military service.

Probably, the same amount of knowledge with certain local variations was received by boys and young men in the poleis of the Eastern Hellenistic powers. The work of schools, the selection of teachers, the behavior and success of students were strictly monitored by the gymnasiarch and elected officials from the citizens of the policy; the expenses for the maintenance of the gymnasium and teachers were made from the state treasury, sometimes for these purposes donations were received from the lavergetes (benefactors) – citizens and tsars.

The gymnasiums were not only educational institutions for young people, but also a pentathlon competition and a center of everyday cultural life. Each gymnasium was a complex of premises that included a palestra, that is, an open area for training and competitions with adjacent areas for rubbing with oil and washing after exercise (warm and cold baths), porticos and exedras for classes, conversations, lectures, where performed by local and visiting philosophers, scientists and poets.

Holidays and celebrations

An important factor in the spread of Hellenistic culture was the numerous festivals – traditional and re-emerging – in the old religious centers of Greece and in the new cities and capitals of the Hellenistic kingdoms. So, on Delos, in addition to the traditional Apollonius and Dionysius, special ones were arranged – in honor of the “benefactors” – Antigonids, Ptolemies, Aetolians. The festivities gained fame in Thespias (Boeotia) and Delphi, on the island of Kos, in Miletus and Magnesia (Asia Minor). The Ptolemies celebrated in Alexandria were equal in scale to the Olympic ones.

In addition to religious ceremonies and sacrifices, the indispensable elements of these festivities were solemn processions, games and competitions, theatrical performances and treats. Sources have preserved a description of a grand festival held in 165 BC. Antiochus IV in Daphne (near Antioch), where the sacred grove of Apollo and Artemis was located: in the solemn procession that opened the holiday, foot and horse soldiers (about 50 thousand), chariotsand elephants, 800 youths in gold wreaths and 580 women sitting in stretchers trimmed with gold and silver; carried innumerable ornate statues of gods and heroes; many hundreds of slaves carried gold and silver objects, ivory. The description mentions 300 sacrificial tables and a thousand fattened bulls. The celebrations lasted 30 days, during which there were gymnastic games, martial arts, theatrical performances, hunts and feasts for a thousand and one and a half thousand people were organized. Participants from all over the Hellenistic world flocked to such festivities.

Not only the way of life, but the entire appearance of the Hellenistic cities contributed to the spread and further development of a new type of culture, enriched by local elements and reflecting the development trends of contemporary society. The architecture of the Hellenistic policies continued the Greek traditions, but along with the construction of temples, great attention was paid to the civil construction of theaters, gymnasia, bouleuteria, and palaces. The interior and exterior decoration of buildings became richer and more diverse, porticoes and columns were widely used, the colonnade framed individual buildings, the agora, and sometimes the main streets (the porticoes of Antigonus Gonatus, Attalus on Delos, on the main streets of Alexandria). The kings built and restored many temples to Greek and local deities.

Hellenistic elements in different cultures

Architecture

The most grandiose and beautiful were considered

- Sarapeum in Alexandria, built by Parmenis in the 3rd century. BC.,

- the temple of Apollo at Didyma, near Miletus, construction of which began in 300 BC e., lasted about 200 years and was not completed,

- Temple of Zeus in Athens (started in 170 BC, completed at the beginning of the 2nd century AD),

- the temple of Artemis in Magnesia on the Meander of the architect Hermogenes (started at the turn of the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC, completed in 129 BC).

At the same time, temples of local deities were built and restored just as slowly –

- the temple of Horus in Edfu,

- goddess Hathor in Dendera,

- Khnuma in Esna,

- Isis on the island of Philae,

- Esagil in Babylon,

- temples of the god Nabu, son of Marduk, in Borsippe and Uruk.

The temples of the Greek gods were built according to the classical canons, with minor deviations. In the architecture of the temples of the oriental gods, the traditions of the ancient Egyptian and Babylonian architects are respected, Hellenistic influences can be traced in individual details and in the inscriptions on the walls of the temples.

The specificity of the Hellenistic period can be considered the emergence of a new type of public buildings – libraries (in Alexandria, Pergamum, Antioch, etc.), Museion (in Alexandria, Antioch) and specific structures – the Pharos lighthouse and the Tower of the Winds in Athens with a weather vane on the roof, a sundial on walls and water clock inside it. Excavations at Pergamum have reproduced the structure of the library building. It was located in the center of the Acropolis, in the square near the temple of Athena. The facade of the building was a two-story portico with a double row of columns, the lower portico rested against a retaining wall adjoining a steep hillside, and on the second floor, behind the portico, which was used as a kind of reading room, there were four closed rooms that served as storage for books, i.e. e. papyrus and parchment scrolls,

The largest library in antiquity was considered the Alexandrian one, outstanding scientists and poets worked here – Euclid, Eratosthenes, Theocritus, etc., books were brought here from all countries of the ancient world, and in the 1st century. BC. it, according to legend, consisted of about 700 thousand scrolls. The descriptions of the building of the Alexandria Library have not survived; apparently, it was part of the Museion complex. Museion was part of the palace buildings, in addition to the temple itself, he owned a large house, where there was a dining room for the scientists who were under Museion, an exedra – a covered gallery with seats for studies – and a place for walking. The construction of public buildings that served as centers of scientific work or the application of scientific knowledge can be seen as a recognition of the increased role of science in the practical and spiritual life of Hellenistic society.

Scientific knowledge

Comparison of scientific knowledge accumulated in the Greek and Eastern world gave rise to the need for their classification and gave impetus to the further progress of science. Mathematics, astronomy, botany, geography, and medicine are undergoing special development. Euclid’s work “Elements” (or “Beginnings”) can be considered a synthesis of the mathematical knowledge of the ancient world. Euclid’s postulates and axioms and the deductive method of proof served as the basis for geometry textbooks for centuries. The work of Apollonius of Perga on conical sections laid the foundation for trigonometry. The name of Archimedes of Syracuse is associated with the discovery of one of the basic laws of hydrostatics, important provisions of mechanics, and many technical inventions.

The observation of astronomical phenomena and the works of Babylonian scientists of the 5th-4th centuries that existed before the Greeks in Babylonia at the temples. BC. Kidna (Kidinnu), Naburiana (Naburimannu), Sudina influenced the development of astronomy during the Hellenistic period. Aristarchus of Samos (310-230 BC) hypothesized that the Earth and the planets revolve around the Sun in circular orbits. Seleucus of Chaldees tried to substantiate this position. Hipparchus of Nicaea (146-126 BC) discovered (or repeated after Kidinna?) The phenomenon of the precession of the equinoxes, established the duration of the lunar month, compiled a catalog of 805 fixed stars with the determination of their coordinates, and divided them into three brightness classes. But he rejected Aristarchus’s hypothesis, citing the fact that circular orbits do not correspond to the observed motion of the planets,

The campaigns of Alexander the Great greatly expanded the geographical representation of the Greeks. Using the accumulated information, Dicaearchus (about 300 BC) made a map of the world and calculated the height of many mountains in Greece. Erastophenes of Cyrene (275-200 BC), based on the idea of the sphericity of the Earth, calculated its circumference at 252 thousand stages (about 39,700 km), which is very close to the actual (40,075.7 km ). He also argued that all the seas are a single ocean and that you can get to India by sailing around Africa or west of Spain. His hypothesis was supported by Posidonius of Apamea (136-51 BC), who studied the ebb and flow of the Atlantic Ocean, volcanic and meteorological phenomena and put forward the concept of five climatic zones of the Earth. In the II century. BC. Hippalus discovered the monsoons, the practical significance of which was shown by Eudoxus of Cyzicus, sailing to India across the open sea. Numerous works of geographers that have not come down to us served as a source for the consolidated work of Strabo “Geography in 17 Books”, completed by him around 7 AD. and containing a description of everything known by that time in the world – from Britain to India.

Theophrastus, a student and successor of Aristotle in the school of peripatetics, modeled on Aristotle’s History of Animals, created a History of Plants, in which he systematized the accumulated by the beginning of the 3rd century. BC. knowledge in the field of botany. Subsequent works of ancient botanists made significant additions only to the study of medicinal plants, which was associated with the development of medicine. In the field of medical knowledge in the Hellenistic era, there were two directions:

- “Dogmatic” (or “bookish”), which put forward the task of speculative knowledge of the nature of man and the ailments hidden in him,

- empirical, aimed at studying and treating a specific disease.

Herophilus of Chalcedon (III century BC), who worked in Alexandria, made a great contribution to the study of human anatomy. He wrote about the presence of nerves and established their connection with the brain, put forward a hypothesis that the mental abilities of a person are also connected with the brain; he also believed that blood circulates through the vessels, not air, that is, he actually came to the idea of blood circulation. Obviously, his conclusions were based on the practice of anatomy of corpses and the experience of Egyptian doctors and mummifiers. Erasistratus from Keos Island (III century BC) was no less famous. He distinguished between motor and sensory nerves, studied the anatomy of the heart. Both of them knew how to perform complex operations and had their own school of students. Heraclides of Tarentum and other empiricists paid great attention to the study of drugs.

Even a short list of scientific achievements suggests that science is gaining great importance in Hellenistic society. This is also manifested in the fact that at the courts of the Hellenistic kings (to increase their prestige), museums and libraries are created, scientists, writers and poets are provided with conditions for creative work. But the material and moral dependence on the royal court left an imprint on the form and content of their works. And it is no coincidence that the skeptic Timon called the scientists and poets of the Alexandrian Museion “fattened chickens in a chicken coop.”

Literature

The scientific and fictional literature of the Hellenistic era was extensive (but comparatively few works survived). Traditional genres continued to be developed – epic, tragedy, comedy, lyrics, rhetorical and historical prose, but new ones also appeared – philological studies (for example, Zenodotus of Ephesus on the original text of Homer’s poems, etc.), dictionaries (the first Greek lexicon was compiled by Philetus Kosky about 300 BC), biographies, transcriptions of scientific treatises in verse, epistolography, etc. At the courts of the Hellenistic kings, refined poetry flourished, but devoid of connection with everyday life, examples of which were the idylls and hymns of Callimachus from Cyrene (310- 245 BC), Aratus of Sol (III century BC), the epic poem “Argonautics” by Apollonius of Rhodes (III century BC), etc.

The epigrams were of a more vital character; they evaluated the works of poets, artists, architects, characteristics of individuals, descriptions of everyday and erotic scenes. The epigram reflected the feelings, moods and reflections of the poet, only in the Roman era did it become predominantly satirical. The most famous in the late 4th – early 3rd century. BC. used the epigrams of Asklepiada, Posidippus, Leonid of Tarentum, and in the II-I centuries. BC – epigrams of Antipater of Sidon, Meleager and Philodemus of Gadara.

The greatest lyric poet was Theocritus of Syracuse (born in 300 BC), the author of bucolic (shepherd’s) idylls. This genre originated in Sicily from a competition of shepherds (bucolas) in the performance of songs or quatrains. In his bucolics, Theocritus created realistic descriptions of nature, living images of shepherds; in his other idylls, sketches of scenes of city life are given, close to mimes, but with lyrical coloring.

While epics, hymns, idylls, and even epigrams satisfied the tastes of the privileged strata of Hellenistic society, the interests and tastes of the general population were reflected in genres such as comedy and mime. The authors emerged at the end of the 4th century. BC. in Greece, the “new comedy” or “comedy of morals”, the plot of which was the private life of citizens, was the most popular Menander (342-291 BC). His work falls on the period of the struggle of the diadochi. Political instability, frequent changes in oligarchic and democratic regimes, disasters caused by military operations in the territory of Hellas, the ruin of some, and the enrichment of others – all this brought confusion to the moral and ethical ideas of citizens, undermined the foundations of the polis ideology. There is growing uncertainty in the future, faith in fate. These sentiments were reflected in the “new comedy”. The popularity of Menander in the Hellenistic and later in the Roman era is evidenced by the fact that many of his works – “The Court of Arbitration”, “Samiyanka”, “Shorn”, “Hated”, etc. – were preserved in papyri of the 2nd-4th centuries. AD, found in peripheral cities and comas of Egypt. The “vitality” of Menander’s works is due to the fact that he not only brought out characters typical of his time in his comedies but also emphasized their best features, asserted a humanistic attitude towards each person, regardless of his position in society, towards women, strangers, slaves. found in the peripheral cities and comas of Egypt. The “vitality” of Menander’s works is due to the fact that he not only brought out characters typical of his time in his comedies but also emphasized their best features, asserted a humanistic attitude towards each person, regardless of his position in society, towards women, strangers, slaves. found in the peripheral cities and comas of Egypt. The “vitality” of Menander’s works is due to the fact that he not only brought out characters typical of his time in his comedies but also emphasized their best features, asserted a humanistic attitude towards each person, regardless of his position in society, towards women, strangers, slaves.

Mime has long existed in Greece alongside comedy. Often this was an improvisation performed on the square or in a private house during a feast by an actor (or actress) without a mask, depicting different characters with facial expressions, gestures, and voices. During the Hellenistic era, this genre became especially popular. However, texts other than those that belonged to Herod did not reach us, and the mimes of Herod (III century BC) preserved in the papyri, written in the Aeolian dialect that was outdated by that time, were not intended for the general public. Nevertheless, they give an idea of the style and content of this kind of works. The scenes written by Herod depict a pimp, a brothel keeper, a shoemaker, a jealous mistress who tortured her love slave, and other characters.

A colorful scene at school: a poor woman, complaining about how difficult it is for her to pay for her son’s education, asks the teacher to whip her idler son, who plays dice instead of studying, which the teacher very willingly does with the help of the students.

Unlike Greek literature of the 5th-4th centuries. BC. the fiction of the Hellenistic period does not deal with the broad socio-political problems of its time, its plots are limited to the interests, morality and life of a narrow social group. Therefore, many works quickly lost their social and artistic significance and were forgotten, only a few of them left their mark on the history of culture.

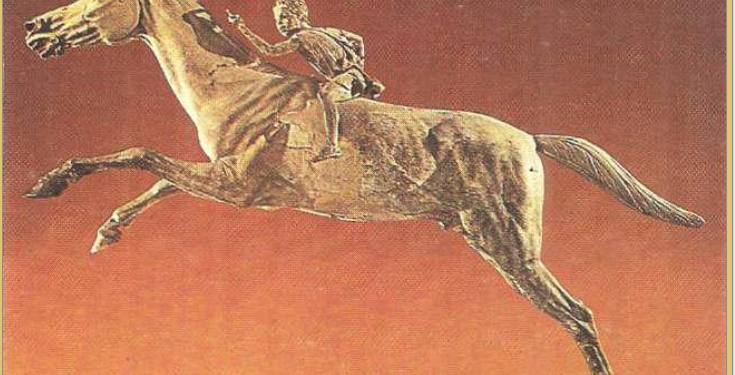

art

The images, themes, and moods of fiction find parallels in the visual arts. The monumental sculpture intended for squares, temples, public buildings continues to develop. It is characterized by mythological subjects, grandeur, and complexity of composition. Thus, the Colossus of Rhodes, a bronze statue of Helios, created by Jerez of Lindus (3rd century BC), reached a height of 35 m and was considered a miracle of art and technology. The depiction of the battle between the gods and giants on the famous (more than 120 m long) frieze of the altar of Zeus in Pergamum (II century BC), consisting of many figures, is dynamic, expressive, and dramatic. In early Christian literature, the Pergamon altar was called “the temple of Satan.” The Rhodes, Pergamon, and Alexandrian schools of sculptors were formed, continuing the traditions of Lysippos, Scopas, and Praxiteles.

- the statue of the goddess Tyche (Destiny), the patroness of the city of Antioch, sculpted by the Rhodian Eutychides,

- sculptured by Alexander “Aphrodite from the island of Melos” (“Venus de Milo”),

- “Nike from the island of Samothrace” and “Aphrodite Anadiomene” from Cyrene by unknown authors.

The emphasized drama of sculptural images, characteristic of the Pergamon school, is inherent in such sculptural groups as Laocoon, Farnese bull (or Dirka), Dying Gaul, and Gallus killing his wife. High skill was achieved in portrait sculpture (a sample of which is “Demosthenes” by Polyeuctus, about 280 BC) and portrait painting, which can be judged from the portraits from Fayum. Although the surviving Fayum portraits date back to Roman times, they undoubtedly go back to Hellenistic artistic traditions and give an idea of the skill of the artists and the real appearance of the inhabitants of Egypt captured on them.

Obviously, the same moods and tastes that gave rise to the bucolic idyll of Theocritus, epigrams, “new comedy” and mimes, were reflected in the creation of realistic sculptural images of old fishermen, shepherds, terracotta figurines of women, peasants, slaves, in the depiction of comedy characters, everyday scenes, rural landscape, mosaics, and wall paintings. The influence of Hellenistic art can be traced in traditional Egyptian sculpture (reliefs of tombs, statues of the Ptolemies), and later in Parthian and Kushan art.

Historical writings

The historical and philosophical writings of the Hellenistic era reveal the relationship of a person to society, political and social problems of his time. Historical writings often focus on events of the recent past; in their form, the works of many historians stood on the verge of fiction: the presentation was skillfully dramatized, rhetorical techniques were used, designed for emotional impact in a certain sense. They wrote in this style –

- the history of Alexander the Great Callisthenes (end of the 4th century BC) and Cleitarchus of Alexandria (mid-3rd century BC),

- the history of the Greeks of the Western Mediterranean – Timaeus from Tauromenia (middle of the 3rd century BC),

- history of Greece from 280 to 219 BC – Philarchus, a supporter of the reforms of Cleomenes (end of the 3rd century BC).

Other historians adhered to a more strict and dry presentation of facts – in this style, the history of the campaigns of Alexander, written by Ptolemy I (after 301 BC), the history of the period of struggle of the Diadochs of Hieronymus from Cardia (mid-III century BC BC), etc. For the historiography of the II-I centuries. BC. interest in general history is characteristic, works belonged to this genre

- Polybius,

- Posidonia of Apamea,

- Nicholas of Damascus,

- Agatarchis of Cnidus.

But the history of individual states continued to be developed, the chronicles and decrees of Greek policies were studied, interest in the history of eastern countries increased. Already at the beginning of the III century. BC. the history of Pharaonic Egypt of Manetho and the history of Babylonia of Berossus , written in Greek by local priests-scientists , appeared, later Apollodorus of Artemita wrote the history of the Parthians. Historical writings also appeared in local languages, for example, the “Books of the Maccabees” about the uprising of Judea against the Seleucids.

Polybius

The choice of theme and coverage of events by the authors was undoubtedly influenced by the political and philosophical theories of their contemporary era, but it is difficult to identify this: most of the historical works have reached descendants in fragments or retellings of later authors.

Only the surviving books from “General History in 40 Books” by Polybius give an idea of the methods of historical research and the historical and philosophical concepts characteristic of that time. Polybius sets himself the goal of explaining why and how the entire known world came under the rule of the Romans. A decisive role in history is played, according to Polybius, by fate: it was she – Tyche – who forcibly merged the history of individual countries into world history, bestowed world domination on the Romans. Her power is manifested in the causality of all events. At the same time, Polybius assigns a large role to a person, outstanding personalities. He seeks to prove that the Romans created a powerful state thanks to the perfection of their state, which combined the elements of monarchy, aristocracy and democracy, and thanks to the wisdom and moral excellence of their politicians. By idealizing the Roman state system, Polybius seeks to reconcile his fellow citizens with the inevitability of submission to Rome and the loss of political independence of the Greek city-states. The emergence of such concepts suggests that the political views of Hellenistic society have moved far from the polis ideology.

Philosophy

This is even more clearly manifested in philosophical teachings. The schools of Plato and Aristotle, reflecting the worldview of the civilian collective of the classical city-state, are losing their former role. At the same time, the influence of those already existing in the 4th century is increasing. BC. currents of cynics and skeptics generated by the crisis of polis ideology.

Stoicism and Epicureanism

However, the predominant success in the Hellenistic world was enjoyed by those who emerged at the turn of the 4th and 3rd centuries. BC. the teachings of the Stoics and Epicurus, which incorporated the main features of the worldview of the new era. To the Stoic school, founded in 302 BC. in Athens by Zeno from the island of Cyprus (about 336-264 BC), many major philosophers and scientists of the Hellenistic time belonged, for example, Chrysippus of Sol (III century BC), Panetius of Rhodes (II BC), Posidonius of Apameia (1st century BC), etc. Among them were people of different political orientations – from advisers to the kings (Zeno) to inspirers of social transformations (Spheres was Cleomenes’ mentor in Sparta, Blossius – Aristonica in Pergamum). The Stoics focus their main attention on the person as a person and on ethical issues; questions about the essence of being are in second place.

The Stoics opposed the feeling of the instability of the status of a person in conditions of continuous military and social conflicts and the weakening of ties with the collective of citizens of the polis with the idea of a person’s dependence on a higher good force ( logos, nature, God) that controls everything that exists. In their view, a person is no longer a citizen of the policy, but a citizen of the cosmos; to achieve happiness, he must learn the regularity of the phenomena predetermined by a higher power (fate), and live in harmony with nature. Eclecticism, the polysemy of the main provisions of the Stoics ensured their popularity in different strata of Hellenistic society and allowed the doctrines of Stoicism to converge with mystical beliefs and astrology.

The philosophy of Epicurus in the interpretation of the problems of being continued to develop the materialism of Democritus , but in it man also occupied a central place. Epicurus saw his task in freeing people from fear of death and fate: he argued that the gods do not influence the life of nature and man, and he proved the materiality of the soul. He saw a person’s happiness in finding calmness, equanimity (ataraxia), which can be achieved only through knowledge and self-improvement, avoiding passions and suffering and refraining from vigorous activity.

Skeptics, who became close to the followers of Plato’s Academy, directed their criticism mainly against the epistemology of Epicurus and the Stoics. They also identified happiness with the concept of “ataraxia”, but interpreted it as the realization of the impossibility of knowing the world (Timon the Skeptic, 3rd century BC), which meant a refusal to recognize reality, from social activity.

Cinemas

The teachings of the Stoics, Epicurus, skeptics, although they reflected some general features of the worldview of their era, were designed for the most cultural and privileged circles. In contrast to them, the cynics performed in front of the crowd on the streets, squares, in ports, proving the unreasonableness of the existing order and preaching poverty not only in words but also in their way of life. The most famous of the Cynics of the Hellenistic period were Cratet of Thebes (circa 365-285 BC) and Bion Borisfenite (3rd century BC).

Cratet, who came from a wealthy family, carried away by cynicism, dismissed the slaves, distributed property and, like Diogenes, began to lead the life of a beggar philosopher. Strongly opposing his philosophical opponents, Cratet preached a moderate cynicism and was known for his philanthropy. He had a large number of students and followers, among them for some time was Zeno, the founder of the Stoic school. Bion was born in the Northern Black Sea region into a family of a freedman and a hetaera; in his youth he was sold into slavery; having received freedom and inheritance after the death of the owner, he came to Athens and joined the school of the Cynics.

The name of Bion is associated with the emergence of diatribes – speeches-conversations filled with the preaching of cynical philosophy, polemics with opponents and criticism of generally accepted views. However, the critics of the rich and the rulers of Kyniki did not go further, they saw the achievement of happiness in the rejection of needs and desires, in the “beggarly bag” and opposed the beggar philosopher not only to the kings, but also to the “unreasonable crowd.”

Social utopia

The element of social protest, which sounded in the philosophy of the Cynics, found its expression in social utopia: Eugemer (late 4th – early 3rd centuries BC) in a fantastic story about Panheya and Yambul (3rd century BC) .) in the description of the trip to the islands of the Sun created the ideal of a society free from slavery, social vices and conflicts. Unfortunately, their works have survived only in the retelling of the historian Diodorus of Siculus. According to Yambul, people of high spiritual culture live on the islands of the Sun among exotic nature, they have no kings, no priests, no family, no property, no division into professions. Happy, they all work together, taking turns doing community service. Eugemerus, in The Sacred Record, also describes a happy life on an island lost in the Indian Ocean, where there is no private ownership of land, but people by occupation are divided into priests and people of mental labor, farmers, shepherds and warriors. On the island there is a “Sacred Record” on a golden column about the deeds of Uranus, Kronos and Zeus, the organizers of the life of the islanders. Outlining its content, Eugemer gives his own explanation for the origin of religion: the gods are outstanding people who once existed, organizers of social life, who declared themselves gods and established their own cult.

Religion

If Hellenistic philosophy was the result of the creativity of the privileged Hellenized strata of society and it is difficult to trace Eastern influences in it, then the Hellenistic religion was created by wide sections of the population, and its most characteristic feature is syncretism, in which the Eastern heritage plays a huge role.

The gods of the Greek pantheon were identified with the ancient eastern deities, acquired new features, and the forms of their worship changed. Some Eastern cults (Isis, Cybele, etc.) were perceived by the Greeks almost unchanged. The significance of the goddess of fate Tyche rose to the level of the main deities. A specific product of the Hellenistic era was the cult of Sarapis, a deity that owed its appearance to the religious policy of the Ptolemies. Apparently, the very life of Alexandria, with its multilingualism, with different customs, beliefs and traditions of the population, prompted the idea of creating a new religious cult that could unite this motley foreign society with the native Egyptian. The atmosphere of the spiritual life of that time required a mystical design of such an act. Sources report the appearance of an unknown deity to Ptolemy in a dream, about the interpretation of this dream by the priests, about the transfer of a statue of a deity in the form of a bearded youth from Sinope to Alexandria, and about his proclamation by Sarapis – a god who combined the features of the Memphis Osiris-Apis and the Greek gods Zeus, Hades and Asclepius. The main assistants of Ptolemy I in the formation of the cult of Sarapis were the Athenian Timothy, a priest from Eleusis, and the Egyptian Manetho, a priest from Heliopolis. Obviously, they were able to give the new cult a form and content that met the needs of their time, since the veneration of Sarapis quickly spread in Egypt, and then Sarapis, along with Isis, became the most popular Hellenistic deities, whose cult existed until the victory of Christianity. combining the features of the Memphis Osiris-Apis and the Greek gods Zeus, Hades and Asclepius. The main assistants of Ptolemy I in the formation of the cult of Sarapis were the Athenian Timothy, a priest from Eleusis, and the Egyptian Manetho, a priest from Heliopolis. Obviously, they were able to give the new cult a form and content that met the needs of their time, since the veneration of Sarapis quickly spread in Egypt, and then Sarapis, along with Isis, became the most popular Hellenistic deities, whose cult existed until the victory of Christianity. combining the features of the Memphis Osiris-Apis and the Greek gods Zeus, Hades and Asclepius. The main assistants of Ptolemy I in the formation of the cult of Sarapis were the Athenian Timothy, a priest from Eleusis, and the Egyptian Manetho, a priest from Heliopolis. Obviously, they were able to give a new cult a form and content that met the needs of their time, since the veneration of Sarapis quickly spread in Egypt, and then Sarapis, along with Isis, became the most popular Hellenistic deities, whose cult existed until the victory of Christianity.

While local differences in the pantheon and forms of worship persisted in different regions, some universal deities are becoming widespread, combining the functions of the most revered deities of different peoples. One of the main cults is the cult of Zeus Gipsist (the Most High), identified with the Phoenician Baal, the Egyptian Amun, Babylonian White, the Jewish Yahweh and other main deities of a particular region. His epithets – Pantokrator (Almighty), Soter (Savior), Helios (Sun), etc. – indicate the expansion of his functions. Another rival in popularity with Zeus was the cult of Dionysus with his mysteries, which brought him closer to the cult of the Egyptian Osiris, Asia Minor Sabazius and Adonis. Of the female deities, the Egyptian Isis, who embodied many Greek and Asian goddesses, became especially revered, and Asia Minor Mother of the Gods. The syncretic cults that developed in the East penetrated the poleis of Asia Minor, Greece and Macedonia, and then into the Western Mediterranean.

The Hellenistic kings, using ancient Eastern traditions, planted a royal cult. This phenomenon was caused by the political needs of the emerging states. The royal cult was one of the forms of Hellenistic ideology, in which the ancient Eastern ideas about the divinity of the royal power, the Greek cult of heroes and oikists (founders of cities) and philosophical theories of the 4th-3rd centuries were merged. BC. about the essence of state power; he embodied the idea of the unity of the new, Hellenistic state, raised the authority of the tsar’s authority with religious rites. The royal cult, like many other political institutions of the Hellenistic world, was further developed in the Roman Empire.

Decline of the Hellenistic states and changes in culture

With the decline of the Hellenistic states, noticeable changes took place in Hellenistic culture. Rationalistic features of the world view are increasingly receding before religion and mysticism, mysteries, magic, astrology are widely spread, and at the same time, elements of social protest are growing – social utopias and prophecies are gaining new popularity.

During the Hellenistic era, works continued to be created in local languages that retained traditional forms (religious hymns, memorial and magical texts, teachings, prophecies, chronicles, fairy tales), but reflected in one way or another the features of the Hellenistic worldview. From the end of the III century. BC. their importance in Hellenistic culture is increasing.

The papyri preserved magic formulas, with the help of which people hoped to force the gods or demons to change their fate, cure diseases, destroy the enemy, etc. Initiation in the mysteries was viewed as direct communication with God and liberation from the power of fate. The Egyptian tales about the sage Haemuset talk about his search for the magical book of the god Thoth, which makes its owner not subject to the gods, about the incarnation in the son of Haemuset of an ancient powerful magician and about the miraculous deeds of the boy magician. Haemuset travels to the afterlife, where the magician boy shows him the ordeals of the rich man and the blissful life of the righteous poor next to the gods.

One of the biblical books – “Ecclesiastes”, created at the end of the 3rd century BC, is permeated with deep pessimism. BC: wealth, wisdom, labor – everything is “vanity of vanities”, the author claims.

Sectarianism

Social utopia is embodied in the activities that emerged in the II-I centuries. BC e. Sects of the Essenes in Palestine and therapists in Egypt, in whom religious opposition to the Jewish priesthood was combined with the establishment of other forms of socio-economic existence. According to the descriptions of ancient authors – Pliny the Elder, Philo of Alexandria, Josephus, the Essenes lived in communities, collectively owned property and worked together, producing only what was necessary for their consumption. Entry into the community was voluntary, internal life, community management and religious rituals were strictly regulated, the subordination of the younger in relation to the elders in relation to the age and time of entry into the community was observed, some communities prescribed abstinence from marriage. The Essenes rejected slavery, their moral, ethical and religious views were characterized by messianic-eschatological ideas, the opposition of community members to the surrounding “world of evil”.

The therapists can be viewed as an Egyptian form of Esseneism. They were also characterized by common ownership of property, denial of wealth and slavery, limitation of vital needs, asceticism. There was much in common in the rituals and organization of the community.

The discovery of the Qumran texts and archaeological research have provided indisputable evidence of the existence in the Judean desert of religious communities close to the Essenes in their religious, moral, ethical and social principles of organization. The Qumran community existed from the middle of the 2nd century. BC. before 65 AD In its “library”, along with the biblical texts, a number of apocryphal works were found and, what is especially important, texts created within the community – statutes, hymns, commentaries on biblical texts, texts of apocalyptic and messianic content, giving an idea of the ideology of the Qumran community and its internal organization. Having much in common with the Essenes, the Qumran community more sharply opposed itself to the surrounding world, which was reflected in the doctrine of the opposition of the “kingdom of light” and “kingdom of darkness”.

However, the significance of the Qumran manuscripts is not limited to evidence of the essence as a social and religious movement in Palestine in the II century. BC. Comparing them with early Christian and apocryphal writings makes it possible to trace the similarities in ideological concepts and in the principles of organization of the Qumran and early Christian communities. But at the same time, there was a significant difference between them:

- the first was a closed organization that kept its teachings secret in anticipation of the arrival of the messiah,

- Christian communities, who considered themselves followers of the Messiah – Christ, was open to everyone and widely preached their teachings.

The Essenes and Qumranites were only the forerunners of a new ideological trend – Christianity, which arose already within the framework of the Roman Empire.

Penetration of Hellenistic culture in ancient Rome

The process of Rome’s subordination of the Hellenistic states, accompanied by the spread of Roman forms of political and socio-economic relations to the countries of the Eastern Mediterranean, had a downside – the penetration of Hellenistic culture, ideology, and elements of the socio-political structure into Rome. The export of art objects, libraries (for example, the library of King Perseus, taken out by Emilius Paul), educated slaves and hostages as war booty had a huge impact on the development of Roman literature, art, philosophy. The processing by Plautus and Terentius of the plots of Menander and other authors of the “new comedy”, the flourishing of the teachings of the Stoics, Epicureans and other philosophical schools on Roman soil, the penetration of Eastern cults into Rome – these are just some, the most obvious traces of the influence of Hellenistic culture.

The meaning of the Hellenistic era

The above does not exhaust the significance of the Hellenistic era in the history of world civilization. It was at this time for the first time in the history of mankind that contacts between Afro-Asian and European peoples acquired not an episodic and temporary, but a permanent and stable character, and not only in the form of military expeditions or trade relations but above all in the form of cultural cooperation, in the creation of new aspects of public life within the Hellenistic states. This process of interaction in the field of material production in an indirect form was reflected in the spiritual culture of the Hellenistic era. It would be an oversimplification to see in it only the further development of Greek culture.

It is no coincidence, for example, that the most important discoveries in the Hellenistic period were made in those branches of science where the mutual influence of previously accumulated knowledge in ancient Eastern and Greek science (astronomy, mathematics, medicine) can be traced. The joint work of the Afro-Asian and European peoples was most clearly manifested in the field of the religious ideology of Hellenism. And ultimately, on the same basis, the political and philosophical idea of the universe, the universality of the world, arose, which found expression in the writings of historians about the ecumene, in the creation of “General Histories” (Polybius and others), in the teachings of the Stoics about space and the citizen of space, etc. .d.

The spread and influence of a syncretic Hellenistic culture were unusually wide – Western and Eastern Europe, Western and Central Asia, North Africa. Elements of Hellenism can be traced not only in Roman culture but also in Parthian and Greco-Bactrian, in Kushan and Coptic, in the early medieval culture of Armenia and Iberia. Many achievements of Hellenistic science and culture were inherited by the Byzantine Empire and the Arabs and entered the golden fund of human culture.