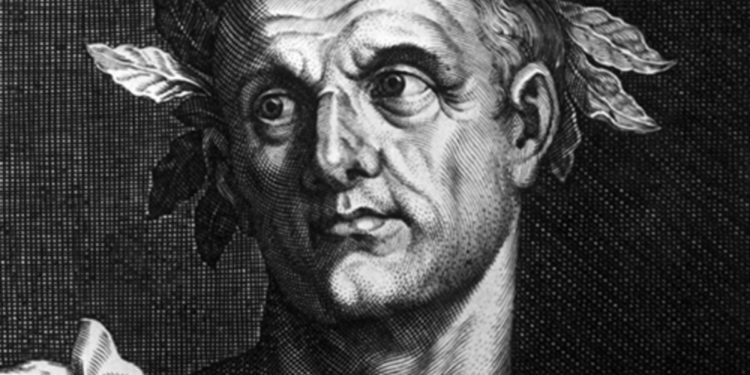

We continue our story about the reign of Julius Caesar. In the second part, you will learn about the conquest of the Gali tribes, the politics of clementia, the large revolt of the Gauls under the command of the young leader Virtsingetoriksa. Learn about the history of the winged Latin expression “Alea jacta est”, as well as the events that developed after the collapse of the Triumvirate, which led to Caesar’s confrontation with Pompey.

The conquest of Gaul

After the consulate, Caesar, as befits a proconsul, was given the administration of the province. But thanks to the influence of the triumvirate – not for one year, as was prescribed by law, but for five years with the right to declare and wage war without the consent of the Senate. Caesar had four legions under his command. Gaul became its province. At first Caesar received only Cisalpine Gaul and Illyric, and then the rest of Gaul, which still had to be conquered.

Through diplomacy and military art, Caesar gradually begins to conquer the Gallic tribes. By 56 BC e. the territories between the Alps, the Rhine and the Pyrenees, through the efforts of Caesar, were completely joined to Rome. This victory came to Caesar quite easily. “As far as the Gauls are boldly and decisively ready to start any war, they are just as weak and unstable in the transfer of failures and defeats,” Caesar wrote in Notes on the Gallic War.

Caesar was the first of the Romans to cross the Rhine, pushing back the invading Germanic tribes. He made (again the first) two campaigns in Britain, subjugating to Rome part of the Celtic tribes who lived there and imposing a tribute to them. The successful commander literally filled up Rome with gold and with his help continued to actively influence political life.

However, busy with the Gallic campaigns, Caesar did not forget to monitor the strength of the triumvirate. By 56 BC e. Caesar’s companions – Pompey and Crassus – were on the verge of breaking. Caesar met with them in the city of Luke, where three politicians confirmed the previous agreements and distributed the provinces: Spain and Africa withdrew to Pompey, Syria – Crassus. Caesar was extended for another five years in Gaul.

In this province, things did not go as smoothly as we would like. Thanksgiving prayers and festivities that were held in honor of Caesar’s victories could not reconcile the spirit of the Gauls and their desire to free themselves from the heavy custody of Rome.

It is in Gaul that Caesar begins to pursue a policy of clementia (in Latin – “mercy”), on the principles of which he will base his policy in the future. He forgave the repentant and tried in vain not to shed blood, preferring to have life owed to him, rather than dead Gauls.

However, nothing could stop the impending storm. In 52 BC e. The Gallic Uprising broke out, led by the young leader Virtsingetoriks. Caesar was in a very difficult position. He had only 60 thousand people (10 legions), and the rebels – 250-300 thousand. The Gauls, having suffered a number of defeats in open battle, switched to partisan actions. Everything that Caesar conquered as a result of this rebellion was lost. But in 51 BC. e. near the city of Alesia, the Romans in three battles with great difficulty manage to defeat the rebels. Vircingetorix was captured, many leaders were killed, the Gaul militia escaped, and the uprising subsided. In the years 52-51 BC e. Caesar had to conquer Gaul again.

Alea jacta est

No sooner had the All-Gall uprising subsided, then Caesar was again in trouble, this time in Rome. In 53 BC e. Crassus died in a campaign against the Parthians. Pompey, not seeing after this the point of observing previous agreements with Caesar, began to strengthen his position and protect only his interests.

The Roman Republic was on the verge of collapse. Either Pompey (legally – he was already appointed by the Senate as the only consul), or Caesar (illegally) could easily take advantage of her weakness. All attempts by Caesar to end the case amicably and find a mutually acceptable solution were unequivocally rejected by the Senate and Pompey. Flouting Roman laws, they gathered troops.

Caesar once again faced a choice: either to obey the requirements of the Senate and say goodbye to his ambitious plans forever, or, having violated the laws, resist the autocracy of Pompey and, possibly, gain the glory of the enemy of the republic.

The future dictator himself perfectly understood all this, standing on January 10, 49 BC. e. with one legion in front of the small river Rubicon, which separated it from the primordial possessions of Rome. According to the Roman historian Appian, Caesar turned to friends: “If I don’t cross this river, my friends, this will be the beginning of disasters for me, and if I cross it, this will be the beginning of disasters for all people.” Having said this, he promptly, as if inspired by above, crossed the Rubicon, adding: “Let the lot be cast” (in Latin: “Alea jacta est”).

Caesar moved to Rome. The Senate and Pompey were shocked by this turn of events and the speed of Caesar’s actions. All preparations for the resistance were abandoned. Italy turned out to be at the mercy of the “lawbreaker”, and the invincible Pompey the Great and the Senate hastily left the country. Caesar was rapidly advancing towards Rome, taking one city after another and almost without shedding blood. Besides the fact that reinforcements approached him from Gaul, all the Roman garrisons, initially subordinate to Pompey, poured into Caesar’s army.

April 1, 49 B.C. e. Caesar entered Rome. All of Caesar’s good intentions to settle the matter with the world collapsed due to the unwillingness of the remaining senators to be mediators in the negotiations with Pompey. The second civil war has begun.

Caesar pursues a number of important reforms. It repeals the still punitive laws of Sulla and Pompey and gives residents of several provinces the rights of Roman citizenship. To attract the plebs and horsemen, Caesar increased the distribution of bread and partially canceled the debts.

Having settled things in Rome, Caesar hurried to Greece, where Pompey was. The first battle unsuccessful for Caesar took place at Dyrrahia. Consul troops fled. Caesar himself, trying to stop the fleeing soldiers, was almost killed by a standard-bearer who swung a pole at him. The situation was so critical that, as Caesar himself said, “the war could have ended today in complete victory if the enemy had at the head a man who knows how to win.” Alas, Pompey was not such a person and could not take advantage of his advantage. For which he had to pay in the battle of Farsal on August 9, 48 BC. e., when Caesar with half the army defeated the enemy forces. Pompey was so discouraged that he “looked like a man deprived of reason” (Plutarch) and fled to Egypt. Caesar, after the victory, began to subjugate Greece and Asia Minor.

Caesar’s victory was already so obvious that the whole Pompeian fleet under the command of Cassius surrendered without battle to his two legions. Having established his order in Asia, Caesar finally drew attention to the absence of Pompey and hurried after him to Egypt. However, the insidious Egyptians already understood on whose side the strength was, and presented Caesar with a bloody gift – the head of his enemy.