Cattle breeding

Even a cursory acquaintance with the hymns of the Rig Veda shows the great importance that pastoralism was attached to in the life of the Aryans and their ideas about the world. Prayers to the gods often ended with requests for the multiplication of flocks. Cattle were obviously considered the measure of wealth. Pastures and stables are often mentioned. The sacred books included spells against diseases of domestic animals. Milk, ghee, yogurt and various types of milk porridge (often with ghee or cottage cheese) were sacrificed to the gods. Phraseology associated with cattle breeding is richly presented in the Vedas. The leader was literally called the “cow shepherd” (gopa), the wealthy person was called the “owner of the cows” (gomat), the war was called “the search for cows” (gavishti), the clan was called the “cow pen” (gotra), etc. In Vedic poetry, the corresponding images are widely represented, comparisons and metaphors: streams of rivers flow like a herd of cows running towards a watering hole. Indra is a tireless bull capable of impregnating many cows. He is fighting his opponents in order to free the herds of cows stolen by those.

Mention of other domestic animals is much less common, but the breeding of goats and sheep is well documented. We are talking about clothes made of wool (urna-fleece) and about the use of milk and meat from small ruminants. The fears of wolves reflected in a number of hymns are clearly inspired by the cattle-breeding life. Mostly oxen, donkeys and mules were used as draft animals. The battle chariot harnessed horses. This their most important role in military affairs was at the heart of the cult of the horse, which was a characteristic feature of the Vedic religion.

We learn from late Vedic sources that the cattle belonged to separate families, although they were usually driven out to common pastures. Special shepherds are mentioned – “cow, goat, sheep”. The dung was dried and widely used as fuel and fertilizer, as well as in sacred ceremonies for home rituals. The cows were milked twice and three times a day. Milk, curdled milk, cottage cheese, butter were used for sacrifices and for food. Obviously, therefore, the brahmanas said, “The cow is the nourisher of all this (the world) . ” On solemn occasions – during the sacrificial ritual, holidays, reception of an honored guest – they also ate meat. Despite a number of taboos related to the consumption of meat, primarily beef, the custom of vegetarianism has not yet taken shape.

It is easy to see that cattle were given great importance in the brahmanas. This was expressed in formulas such as “livestock is a home” or “wealth is livestock.” The legendary story of the division of inheritance between the descendants of Manu testifies to the fact that the real wealth did not really lie in the land, but in domestic animals. There was still a lot of free land, it was only necessary to clear it from the forest. Moreover, arable land has long been regarded as – to a certain extent – a common property. The development of private property was most vividly expressed in the increase in the number of livestock belonging to a separate family.

Agriculture

The traditional terminology and imagery, the mythological plots of the Rig Veda, obviously, contribute to a certain archaization of the picture of the life of the Indo-Aryans, which develops when reading the monument. We have no reason to see in the Aryans only nomadic shepherd tribes. Even in the early parts of the source, in the so-called “family mandolas”, cultivated land (urvara) is mentioned as opposed to wasteland (khila). Perhaps even a primitive system of irrigation of fields was used by means of wells, artificial channels and ponds – the corresponding designations are known in the language of the Rig Veda. The plowing of the soil was carried out not only with a simple hoe (khanitra), but also with a plow. The latter is designated mainly by the term langapa, apparently borrowed from the local population. It’s not quite clear whether we are talking about a simple plow or a plow share with a metal tip was already known. The most probable seems to be the use of a ploughshare made of hardwood. Even later, the Shatapatha Brahmana speaks of the ploughshare made from the Udumbara tree. A plowman leading a furrow with the help of a team of fat oxen is no less characteristic of the poetry of the Rig Veda than a shepherd with a herd of cows. The god Pushan was considered the patron saint of agricultural labor.

Of the cereals, Java is most often mentioned in hymns. Apparently, we are talking about barley. Oilseeds were also grown – namely sesame. Refined and unrefined grains, a special mixture of barley and sesame, drinks with flour, gruel or flour products fried in oil were sacrificed to the Vedic gods. A pestle and mortar were used to grind the grains. An intoxicating drink, sura, was prepared as a daily drink. Probably, in the old days this word meant barley beer, although later it was called rice vodka. There are mentions of ripe fruits, but it is hardly possible on this basis to talk about gardening – we could also talk about the gifts of the forest. The honey drink was of great importance (including in the religious cult), but, apparently, we are also talking only about the collection of wild honey.

For the late Vedic period, it can be said with even greater confidence that agriculture was the main branch of the economy. Agricultural terminology associated with both the cultivation and the processing of grain is presented in the brahmanas much broader than in the samhitas. We meet mentions of cutting ears with sickles, threshing sheaves, winding with baskets, storing grain in bags and flour in special vessels. There is a lot of information about various agricultural cultures. Among the cereals, in addition to barley, it is necessary to note wheat (starting with the late Samhitas) and rice. Probably, in some areas, depending on natural conditions, preference was given to one or another culture. Rice was grown in several varieties.

It is especially important that the latter can be alternated with barley, thus collecting two crops per year. This is directly stated in the Taittiriya-samhita: “the grain ripens twice a year . ” Despite the fact that rice, apparently, was not particularly productive, this significantly increased grain harvests, could contribute to population growth and the accumulation of food surpluses. However, one should not represent the agriculture of that time in overly idyllic tones. Crop failures and famine were obviously not uncommon. At least in the literature Brahmin repeatedly speaks of hunger: hunger – this death, hunger – the darkness, hunger – the enemy of the people, and the like .

In addition to cereals, legumes, sesame seeds, vegetables (cucumbers, jujubes), industrial crops were grown (sources mention linen fabrics). The Upanishads repeatedly refer to tropical fruits such as mangoes. Both nature and the economic structure, reflected in brahminical prose, differ from what can be seen in the Rig Veda.

The creators of late medieval literature lived mainly in villages and were engaged in agriculture. The opposition of the village (thunder) to the uncultivated land (aranya) was associated for them with the opposite of culture and savagery, even life and death. However, the forests were close to plowed fields. On the edges of the village, the villagers grazed cattle, went to the forest to hunt, collect fruits and fuel for the hearth. The forest seemed dangerous due to predatory animals and robbery savages. Folk fantasy inhabited it with many demonic creatures. The concept of vrata, reflected in the brahmanas, is curious. The Pancavimsa-brahmana, for example, says that they do not know piety or agriculture. This assessment clearly shows the importance that the compiler attached to agriculture as one of the defining characteristics of that Vedic culture,

Crafts and metallurgy

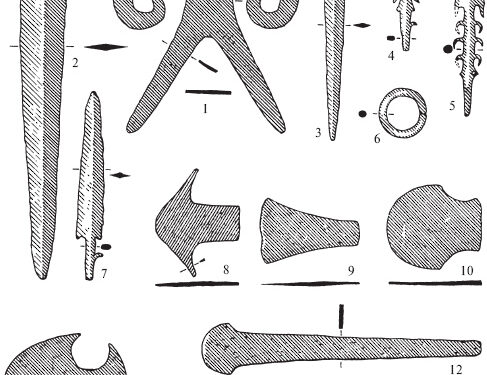

The already noted vagueness of the terminology of the Rig Veda causes contradictory judgments about whether iron was already known at that time. A metal called ayas is repeatedly mentioned in the hymns. The poet calls the flames of the sacrificial fire by the teeth of the god Agni, made of ayas. This suggests that ayas is yellow or red, i.e. copper or bronze. Sometimes the word was used in this sense even later. The Atharva Veda, for example, says that a polished vessel of ayas shines like gold. Of the precious metals, gold was known, which was used to make jewelry and amulets. It was called, in particular, suvarna (literally, “beautiful color”). Obviously, due to the fact that gold does not corrode, magical ideas about immortality were associated with it.

Little is known about crafts in the era of the Rig Veda. The professionals could be mainly gunsmiths and jewelers. The creation of war chariots required skilled carpenters (takshan), specialists in the manufacture of spoked wheels and the like. We find mentions in hymns of various types of arrows – with plumage, with tips of metal or from a specially treated deer antler, about scaly shells made of leather or from rope loops. Relatively complex techniques in these branches of production make us assume a social division of labor. On the contrary, making fabrics and clothing used in everyday life clearly remained the occupation of women in every family.

In the ritual, wooden vessels, various kinds of ladles and spoons were widely used, but in everyday life the dishes were usually earthenware. There are references to pots made of baked and unbaked clay, with or without lids, with handles for hanging over the hearth, large water jugs, etc. Since we are talking about traditionally sacred objects, brahminical prose paints, apparently, a somewhat archaized picture of the material conditions of life. Even in late Vedic literature, there is an idea that the gods are entitled to hand-made vessels, and the asuras, the opponents of the gods, on a potter’s wheel. This can hardly be attributed to household ceramics of that time.

Already in the White Yajurveda, a distinction is made between two types of ayas – red and black. If the former can mean copper or bronze, then the latter is clearly iron. The word “ayas” thus becomes the general name for the metal. We also meet “black ayas” in the Shatapatha-brahmana, which distinguishes it from just ayas – obviously copper. Other metals are also mentioned, most notably lead. In the Atharva Veda, magical properties are attributed to lead, products made from it were used as amulets.

In the late Vedic literature there is a special term for the professional potter, and one can assume the inheritance of this craft. Great importance was attached to ritual purity, in particular the purity of occupations, sources of livelihood. From this point of view, agriculture and cattle breeding were seen as pious and impeccable deeds – on the contrary, artisans were considered “unclean”, some of them were directly forbidden to be present at Vedic sacrifices. In a broad sense, other professionals, who obviously did not manage their agricultural economy, were also counted among artisans (or “craftsmen”) – doctors and barber, acrobats and laundresses, dancers and incense makers.

Trade

There is very little information about trade in the Rig Veda. It had an exchange character, with cows being the usual measure of value. In cows, an assessment was given for any large payments: from wedding gifts to vira – compensation for the killed (ancient Indian vaira). Gradually, another equivalent appears – gold neck jewelry (niche). This can, in particular, refer to the reports that the tsars presented singers with numerous niches-grivnas.

Further development of trade is reflected in the late Vedic literature. There are special designations of merchants who, for example, “exchange metal (ayas) for salt”. There are terms for greedy moneylenders. Niches remain a subject of prestige and a measure of value along with cows. But for trading operations, smaller and more practical measures were used, namely gold by weight, starting with the smallest fractions. Even then, those names of gold grains (Krishnala) or ingots (shatamana – “one hundred measures”), which are well known in Sanskrit literature of later times, appear.

But on the whole, it must be said that wealth in the late medieval times could rarely be accumulated as a result of successful commerce. The very terms of sale and purchase are quite often found in sources only in connection with ritual exchange. Obviously, only those who had the power, the right to dispose of the property and labor of their fellow tribesmen were really wealthy.