During the Civil War in the United States, Confederate rangers launched two reckless raids on federal rear lines to capture enemy generals. The first was the famous raid of John Mosby, who in March 1863 captured the brigadier General Edwin Stoughton. Almost two years passed, and Lieutenant Jesse McNeill surpassed the achievement of Mosby. In February 1865, he stole two federal major generals at once – George Crook and Benjamin Kelly. Both of these attacks have become a symbol of the desperate struggle of the Confederation.

A feature of the American Civil War was the active partisan actions of the Confederate rangers and partisans in the federal rear. Among the numerous combat and sabotage actions carried out by the rangers of the southerners, two raids stand alone, the purpose of which was to abduct enemy generals. We will tell you more about them.

The Sun of Austerlitz by John Mosby

One of the most epic sabotage actions during the whole war was the impudent capture by rangers of John Mosby of federal brigadier general Edwin Stoughton on March 9, 1863.

In 1861, twenty-three-year-old West Point graduate Edwin Stoughton became the youngest colonel in the US Army. The following year, he proved himself to be the commander of the 4th Vermont Infantry Regiment in the Campaign on the Peninsula, unsuccessful for the federal troops. In November 1862, Stoughton received the rank of brigadier general and led the 2nd Vermont Infantry Brigade, stationed in Northern Virginia. In early March 1863, he deployed his headquarters in the city of Fairfax. In addition to Stouton, Colonel Percy Wyndham, commander of the cavalry brigade, who actively fought against the southerners operating in the federal rear, was in Fairfax.

The news of the appearance of Stouton and Wyndham in Fairfax quickly learned the Confederate captain John Mosby. Since January 1863, Mosby commanded the separate 43rd Virgin Cavalry Battalion, which in fact was a detachment of horse guerrilla rangers. He regularly made daring raids on enemy rear lines and constantly sought out new targets. Mosby also knew about the emergence of significant federal forces in Fairfax – however, the picture was not clear to him to the end. Private James Ames, a deserter from the Federal 5th New York Cavalry Regiment who joined the rangers, finally helped clarify her. Ames told Mosby about Fairfax and the location of outposts around the city. The ability to decapitate federal troops in Fairfax County was so tempting that Mosby immediately devised a daring strike plan.

On the evening of March 8, Mosby led a detachment of 29 horsemen in a raid. By 2 a.m. on March 9, the Confederates, without incident, reached Fairfax. On approaching the city, southerners cut the telegraph wires, depriving the federals of communications.

The city was filled with soldiers, but Mosby knew the numbers of regiments stationed in the district. Therefore, when the ranger called out at the entrance, Mosby answered: “5th New York Cavalry” and calmly drove up to the guard. Seconds later, the rangers disarmed the sentries and took them with them so that they would not raise an alarm. The garrison slept peacefully, unaware of the presence of the enemy.

Once in place, Mosby did everything as a professional saboteur. He divided his squad into several groups, sending them with different tasks. The Confederates captured all federal guards and individual soldiers along the way. Ironically, the aforementioned James Ames captured his former commander – Captain Barker from the 5th New York Cavalry Regiment, who was now one of Stouton’s adjutants. Also, the southerners captured the telegraph station, captivating the sleeping telegraph operator. Mosby’s next target was to capture Wyndham. It turned out that the colonel had left the city the day before, having left for Washington on official business. Then the rangers went after Stoughton, whose location was shown to them by one of the captive guard soldiers.

In Fairfax, Stoughton lodged in the house of Dr. William Ganell on Main Street near the District Court building. On the eve, a mother and sister came to Stouton from Washington, and in their honor the young general threw a champagne party. Stoughton went to bed pretty drunk.

In the middle of the night of Adjutant Stouton, Lieutenant Samuel Prentiss was awakened by a persistent knock on the door. Opening, Prentiss saw an unknown officer who told the sleepy lieutenant that he had brought an urgent report from the 5th New York Cavalry Regiment, and ordered him to be taken to the general. In the house, Mosby no longer lurked and entered the room with a fair amount of noise, hoping to produce the desired effect, but Stouton did not even wake him up. Then Mosby tore off the general’s blanket, but this also did not give effect – Stoughton turned over on the other side and snored.

As Mosby later recalled, he could not afford to stand on ceremony, so he woke the general with several slaps. Stouton woke up, not understanding what was happening, raised himself up on his pillow and in an “authoritative tone” asked what this gross intrusion meant. Mosby bent down to him and said: “General, have you ever heard of Mosby?” “Yes, did you catch him?” Stouton answered. “No, it’s me Mosby, and I caught you.”

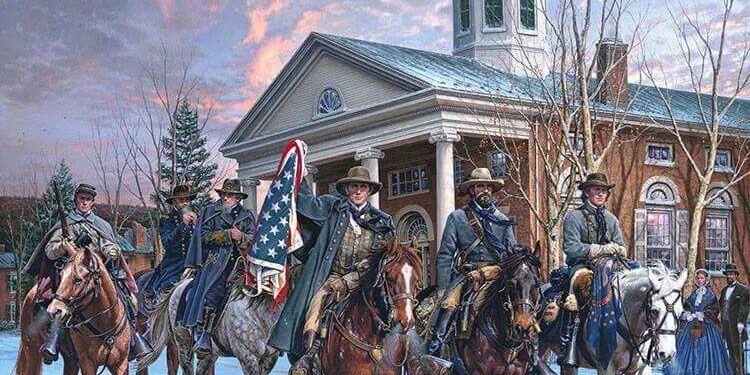

To rob Stouton of all hope, Mosby added that the city was occupied by southerners’ cavalry under the command of Brigadier General Fitzhugh Lee, who was Stouton’s fellow student at West Point. Leaving the house, Mosby took a piece of coal from the fireplace and wrote his name on the wall.

While Mosby was in charge of the general, the other rangers captured the federal headquarters, where they captured seven messengers. However, capturing Stoughton, Mosby no longer paid attention to other prisoners, concentrating on the task of removing the general from the city at all costs. Lieutenant Prentiss took advantage of the weakening of attention – when the prisoners were put on horses, he fled and hid in the dark, “not even wishing us good night”as Mosby ironically remarked. Now the Confederates could not lose time. Riders drove quickly through the city streets, carrying three dozen prisoners and chasing the captured horses. At this moment, Prentiss raised the alarm, but he did not know how many southerners really were, thinking that at least their equestrian brigade. Therefore, among the soldiers of the garrison a panic broke out, which the rangers took advantage of, calmly leaving Fairfax.

Once outside the city, Stoughton realized that Fairfax was not captured by the Confederates, and that all their forces consisted of a handful of people. “You did a desperate thing, but of course you will be caught, soon our cavalry will come after you, ” he said to Mosby, who was riding next to him. “Probably not ,” Mosby said succinctly.

During the retreat, only one of the prisoners made an attempt to escape. When the southerners drove past the sleeping federal camp, Captain Barker tried to escape, but one of the rangers, an ethnic Hungarian named Jake, stopped this attempt in time by shooting the captain’s horse. Mosby drove up to Barker and politely asked if he was hurt. “No ,” muttered Barker, to whom another horse was let down. Then everything went without incident. It was already dawning when the detachment left for the Grovetonsky heights near the town of the same name. Now the Confederates could feel safe. Mosby inclined to pathetic remarked to the accompanying ranger George Slater: “George, this is Austerlitz’s sun . “

The result of the raid was staggering – a brigadier general, 2 captains, a telegraph operator, 30 other military personnel and 58 horses were taken prisoner. Southerners have not lost a single fighter. The event became widely known on both sides of the front. One of the most caustic reactions came from US President Abraham Lincoln, who noted that “I’m not so worried about losing a brigadier general, because I can do one more in five minutes, but here are the horses – they cost $ 125 apiece!”

In captivity, Stoughton spent only two months, and then was exchanged. However, his career ended – upon returning to Washington in May 1863, the general was immediately dismissed from the army. Later, Stoughton worked as a lawyer in New York, and in 1868 died of tuberculosis.

McNeill Raid

The Mosby Rangers were far from the only partisan detachment among the Confederates. The McNeil rangers operating in West Virginia had an equally legendary reputation. Officially, this partisan detachment was called company “E” of the 18th Virgin Cavalry Regiment, and commanded by Captain John Hanson McNeil. His rangers acted in the rear of the federal troops, “raising hell” wherever they had at least a slight chance. Their main goals were trains, railway stations and outposts of the federals. McNeill combined actions in the enemy rear with regular service. So, during the Gettysburg campaign, his detachment of “Virgin Partisan Rangers” of 90 people was part of the Imboden Command of Brigadier General John Imboden and guarded the North Virginia army convoys from navy cavalry raids.

On October 3, 1864, Captain McNeill was mortally wounded in one of the fights. After that, the command of the unit was transferred to his son, twenty-two-year-old lieutenant Jesse McNeill. This young man had a reputation as a great horseman and gunner, and also had an extremely bold character. Even his father talked about his son: “The most reckless daredevil that can only be . “

The story that will be discussed began in 1862, when Captain John McNeil developed a plan to abduct Brigadier General Benjamin Kelly, the federal commander of the Department of West Virginia. The reason was that Kelly was rude to McNeil’s wife. Mrs. McNeill lived in the federal state of Ohio, but wanted to visit her husband behind the front line. Since Kelly refused the lady a passport, she hit the road without documents. The trip did not last long – on the way the patrol arrested the woman and sent her home.

Captain McNeill failed to implement the revenge plan. However, becoming the commander of the detachment, the son decided to realize his father’s plan. At this point, the situation has changed. The Department of West Virginia and the “army of West Virginia” operating there from three divisions was headed by Major General George Crook. Benjamin Kelly, also promoted to major general by this time, had become Crook’s deputy, so Jesse McNeill decided to steal not one general, but two at once.

The headquarters of both generals was located in the city of Cumberland (Maryland), and several people from this area served in the McNeill detachment, including a Cumberland resident fighter named John Fay. In February 1865, Jesse McNeil sent Fay with another soldier, Richie Haller, to scout the city. They had to find a place for the generals to stand and lay the optimal route to Cumberland through enemy territory. Fay and Haller successfully completed this reconnaissance mission, having obtained the necessary information. After that, McNeil with his deputy lieutenant Isaac Welton and several sergeants drew up a plan and began to act.

On the night of February 21, 1865, under the cover of a blizzard, a detachment of 65 rangers raided. Southerners drove quickly along the snowy New Creek Road when they stumbled upon a federal outpost. The frozen sentry shouted to the riders: “ Wait ! Who goes?”It is worth noting that some rangers wore allied overcoats, which means that at night, and also in snow, they could easily impersonate the feds. But then something happened that immediately jeopardized the entire mission: upon hearing the cry of the sentry, Lieutenant McNeil instinctively grabbed the revolver and fired. He shot almost point blank, but unexpectedly missed everyone. However, the guards of the outpost were so scared that they immediately surrendered. Southerners disarmed and tied them up. Fortunately for the Rangers, the wind muffled the sound of a shot, they went unnoticed and could continue to fulfill their plan.

At the next two outposts, the southerners managed to deceive the guards – at the entrance to the posts, the riders began to loudly hum the Unionist songs. Dark night and heavy snow played on their side, because the sentries did not look too closely at the shades of their overcoats. One and a half hours before dawn, the rangers happily reached the city and immediately set to work.

McNeil divided his detachment into several groups, which were assigned different tasks. Fei’s group seized a telegraph post where they cut off wires and destroyed equipment. Another detachment went to the military depots in the city – later it turned out that the rangers were able to open the doors, but could not bear anything. Two more detachments went to the places of the generals. Kruk spent the night in the River House in the city center, and Kelly spent the night in the Barnum Hotel. In both cases, everything went as if by notes. Southerners disarmed the sleepy guard and entered the buildings. At gunpoint, both generals were removed from their beds and forced to wear uniforms. Everything happened so quietly that the officers and orderlies who slept in the next rooms did not hear anything. Together with General Kelly, his adjutant Captain Melvin was captured.

It is interesting that both captive generals reacted to what was happening with some degree of humor. According to Kelly’s memoirs, when he was taken out into the street, and he ran face-to-face with Crook, both generals smiled at each other almost simultaneously, “and would have laughed loudly if it had not been for the order to keep silent and the rangers with revolvers around . ”

Losing no time, McNeil ordered the prisoners to mount their horses. In addition to the generals and captain Melvin, the southerners took with them two privates captured in the city. The Confederate’s trophies were the flag of the General Headquarters, the regimental banner and the thoroughbred horse of General Kelly nicknamed Philip. All actions in the city went very quickly and without firing.

Leaving Cumberland, the Confederates moved downstream along the river. There was a federal military camp, and their watchman shouted: “Who is it?” To this, McNeill replied: “Rota B, 3rd Ohio Cavalry, with a password, and we are in a hurry . ” Instead of asking for a password, the officer on duty asked, “What happened?” McNeill replied: “Old grandmother Kelly had a nightmare or a bad dream that the rebels could come for him, and he sent us in this bad weather to scout the other side of the river. Sometimes I want them to catch him. You didn’t think that he was just becoming a nervous old grandmother when he heard that several Johnny crossed the river? ” “Yes I agree! Every time I’m on a post in weather like this . ”“Well, now let us get through, we want to get back as soon as possible,” McNeil demanded, and the riders galloped rushed past the guards. At the same time, both generals were immediately behind McNeil and heard the whole conversation. After the war, Kelly said that hearing all this, Crook gently nudged his leg with his knee and giggled.

A similar conversation took place at the next outpost. Here Jesse McNeill got into a rage, and, still introducing himself as an Ohio captain, told the officer there: “I would like General Grant to remove Grandma Kelly from Cumberland and appoint Crook as commander . ” The officer at the outpost agreed and skipped them. Hearing his answer, Crook laughed out loud, and again hit Kelly on the leg with his knee. This dialog shows an interesting detail. Of the two generals, Crook was the senior at that moment, but McNeil did not know this. He proceeded from the assumptions of two years ago that the eldest is Kelly. At the same time, the federal officer at the outpost also did not know which of the two major generals to whom he was subordinate was more important than the other.

Meanwhile, in Cumberland, 10 minutes after the Rangers left, the hotel watchman raised the alarm. By this time, McNeill was already about 6.5 km from the city. It took about an hour to repair the telegraph and form a persecution group of 50 people. Cumberland’s senior officer, Major Robert Kennedy, quickly figured out the potential route of the enemy’s withdrawal and began sending dispatches to all neighboring military camps, demanding to assemble persecution groups and move to the cities of Romney and Murfield.

The Kennedy southerners’ departure route was indeed a guess. On the way back, the Confederates drove through the city of Romney, which during the war changed owners 56 times. At that moment, it was formally controlled by the feds, although there was no garrison in the city, and a significant part of the inhabitants sympathized with the Confederations. In the city center, near the courthouse, McNeil staged a parade, showing residents of both captured generals and captured flags. This day has become one of the legendary in the history of the city. The riders drove through Romney in triumph and moved on towards Murfield, in the vicinity of which they stopped at one of the farms for a short rest and dinner.

From the farm, the rangers moved towards the Shenandoah Valley to join the forces of General Jubal Earley. Crooke recalled: “McNeil and all his people treated us with the utmost politeness and attention, but forced to ride at breakneck speed to avoid persecution”. At this point, the rangers were in the most vulnerable position. 12 minutes after McNeil left, a detachment of pursuers rushed to the farm, sent to Murfield at the request of Major Kennedy. A farmer sympathizing with the Confederates misled the northerners and indicated the wrong direction of movement. As a result, McNeil safely escaped the chase, and on the night of February 22 reached the Confederate camp in the mountains. The total distance traveled by the rangers, starting from the evening of February 20 and ending at night on February 22 (approximately 30 hours), was 145 km.

This raid, which was actually the result of youthful mischief, was an astounding success. Confederate General John Gordon, speaking of McNeil’s raid, emphasized that “in impudence and swiftness, this was the most exciting incident in the entire war . ” And John Mosby said at a meeting with Lieutenant Welton: “You guys gave me a strong slap in the face. The only way for me to compare with you is now to go to Washington and bring Lincoln . ” And even the captive General Crook told McNeil: “Gentlemen, this is the most brilliant feat in war . ”

On the other hand, the abduction of two minor generals did not affect the course of the war, the position of the Confederacy remained critical. She had only one and a half months to exist.

For this brilliant share, Jesse McNeil was promoted to captain. His detachment fought until the end of the war, surrendered on May 8, 1865, and was immediately released from captivity under the obligation to no longer fight against the federal government.

For both captive generals, this story ended quite well – they were exchanged on March 20, 1865. After the war ended, Crook returned to the army, fought with the Indians and built a good career. As for Kelly, he retired and joined the tax administration.