The economic situation of the state

New phenomena were primarily determined by the final, lasting unification of the country, its rallying into one political and economic whole. This becomes especially clear if we consider that there were no significant changes in the instruments of production in comparison with the Early Kingdom. The changes were apparently mostly quantitative. Only a sharp increase in the production of copper tools could lead, for example, to great changes in the construction business – the beginning of unprecedented construction from soft limestone. It is known that blocks from this stone were cut with copper saws, which were made from ingots that were specially forged for strength. A large number of different copper tools and their small models have come down to us from the tombs of the Old Kingdom, but a variety of stone tools were still widely used, wooden hoes, sickles with flint teeth, a primitive wooden plow. The brass tool was of great value at this time.

The complete unification of Egypt and a more purposeful organization of production within the unified country greatly contributed to the general rise of all branches of the Egyptian economy.

Industrial relations – the basis of the economy of Ancient Egypt

For the first time, the monuments of the Old Kingdom make it possible to illuminate some important aspects of production relations in Egyptian society. Numerous documents show the existence of the tsarist economy and especially the households of private individuals – nobles who held high positions at the court, in the administrative apparatus, both in the center and locally – in the nomes.

Numerous painted reliefs completely cover the inner walls of the funeral noble tombs and are provided with brief explanatory inscriptions. They make it possible to imagine the life of a large economy – a nobleman’s “own house” (perjet). These tomb images were closely associated with the Egyptian cult, which reflected the Egyptians’ ideas about the other world as an eternal copy of earthly real life, and were, in essence, a detailed visual description of this life, therefore they are most directly related to the actual economy of the nobleman.

Tomb reliefs tell us about the nobleman himself and about his immediate surroundings. Usually he is shown as the head of a large family, which includes his wife and children, brothers and sisters, sometimes mother and father, relatives, household members. There are also numerous personal servants, musicians, singers and singers, dancers, barbers, hairdressers, fan-bearers, bodyguards. It is interesting that the younger members of the family, along with the domestic servants, serve the owner of the estate or participate in the management of his household.

Noble economy

A large noble economy consisted of a main estate and numerous estates (courtyards and villages) located in different parts of the country, both in Upper and Lower Egypt. An extensive staff of various kinds of employees – scribes, overseers, bookkeepers, custodians of documents, managers, headed by the “housekeeper” who carried out the overall management of the entire economic life of “his own house” – organized and supervised the work of farmers and shepherds, fishermen and poultry farmers, gardeners and gardeners , bakers and brewers, coppersmiths and jewelers, potters and stone cutters, weavers and sandalicians, carpenters, joiners, shipbuilders, painters and sculptors – all those who are so vividly represented on the tomb reliefs for their daily work in the field and in the pasture, in the craft workshop and in the house of the nobleman himself.

A characteristic form of the organization of labor in field cultivation during the period of the Old Kingdom were workers’ detachments, who worked during sowing and harvesting. As far as can be judged from the scenes of agricultural work and the inscriptions to them, the sowing grain was delivered to the farmers from the granary of the noble farm, draft cattle (usually two long-horned cows) were brought from the noble herd, the harvested crop, brought by donkeys, belonged to the nobleman and after processing in the barn entered his own bins.

Workers’ detachments also worked in the transportation of heavy loads, loading ships (the main vehicle in Egypt) and in many other jobs, and they, as needed, could be transferred to one or another job.

The handicraft production of the noble economy was concentrated in the general craft workshops – the “chamber of masters”, in which artisans of various specialties worked. Only men worked here. Women worked in separate weaving workshops. The farm had a special food division engaged in the manufacture of various products. In all handicraft works, there was a fractional division of labor; several people often worked on the same product at different stages of its manufacture. And in a craft workshop, all means of production belonged to the owner of all farms. Products made by craftsmen were delivered to noble warehouses. This was the case in other sectors of the economy. Consequently, all types of workers involved in the noble economy,

Judging by the relief tomb images, the workers of the noble economy received allowance from the noble warehouses and industries – from vegetable gardens, pastures, fishing grounds, from the granaries, the food department (grain, fish, bread, vegetables, beer). We see how farmers are given clothes – a short apron – and a special oil for anointing, since, working under a cloudless Egyptian sky in the hot sun, an almost naked farmer was forced to lubricate his body with some kind of fatty composition. We do not know whether the employee, in addition to the owner’s allowance, had any additional means of subsistence.

But the same tomb reliefs occasionally depict a market for small exchange, the participants of which, apparently, were also toilers of the noble economy. There was a brisk trade: grain, bread, vegetables, fish were exchanged for fish hooks, shoes, mirrors, beads, and other handicrafts. The measure of value was grain or linen. The presence of such a market can be explained by the existence of a certain surplus of food products among some of the workers, and also, probably, by the existence of a lesson system in craft production. The production rate was, apparently, close to the full productive capacity of the worker, but, having completed his lesson, he could probably make additional items that were already considered to be his own and could be exchanged on the market. If it really was,

Differences from the royal and temple households

The royal and temple economy of the era of the Old Kingdom, from which much more scant information has come down to us, apparently, were organized according to the same principle. Now our ideas about the organization of the temple economy are becoming more definite thanks to the sensational opening by the Czechoslovak expedition of the archives of the pyramidal temple of Neffir-kara in Lbu Sir. We have almost no information about medium and small farms of this era.

Taking into account the undoubtedly large role of the noble households in the economy of the country during the era of the Old Kingdom, it is necessary to identify their connection with the royal (state) economy. It is known that in Egyptian monuments the “own house” of a nobleman appears as something “external” in relation to the “internal”, state (royal) economy. The grandee’s “own house” included land and property inherited from his parents. The owners of this legacy were mainly the eldest sons of the deceased head of the family. That is why, in particular, the younger brothers of the noblemen were forced to serve in his house, to feed on his farm. A nobleman could dispose of property received by will from other persons, as well as inherited from him “for a fee”, i.e. bought.

One gets the impression that the nobleman had the right to dispose of the inherited, bequeathed, purchased property and land at his discretion, as his full property, his property “in truth” (it was from this property that the nobleman probably allocated land and funds to support his funeral cult, providing for the maintenance of a large staff of funeral priests at his tomb). Along with the property “in truth”, the nobleman had property “in service”, which, apparently, he could not completely dispose of, since it did not belong to him personally, but to his position and could be taken away along with the position, therefore, his property ” in truth “and” according to office “the nobleman clearly distinguished. At the same time, the monuments testify that the well-being of the nobleman depended primarily on his official property, and outside of a career, we cannot imagine the nobleman of the Old Kingdom. It must be borne in mind that positions in Egypt, as a rule, were hereditary, passed from father to son, but at the same time such a transfer of office was approved by the king every time. Thus, personal and official in a nobleman’s “own house” is closely intertwined. It is no coincidence that the Egyptian concept of “property” (jet) itself is broader than ours – it can serve both to denote complete ownership (in our understanding), and to denote only possession, use (for service). personal and official in the “own house” of the nobleman is closely intertwined. It is no coincidence that the Egyptian concept of “property” (jet) itself is broader than ours – it can serve both to denote complete ownership (in our understanding), and to denote only possession, use (for service). personal and official in the “own house” of the nobleman is closely intertwined. It is no coincidence that the Egyptian concept of “property” (jet) itself is broader than ours – it can serve both to denote complete ownership (in our understanding), and to denote only possession, use (for service).

Dependent population

The term for a slave (bak, plural baku ) has been known since the early kingdom. The few documents of the Old Kingdom indicate that slaves could be bought and sold (for example, a document from the VI Dynasty that mentions the purchase of slaves has been preserved), therefore, in Egypt during the Old Kingdom there was a slave market. Among the slaves were foreigners, but mostly they were Egyptians by origin. True, the mechanism of enslavement of fellow tribesmen in the conditions of the Old Kingdom is difficult to restore now.

The predominance of huge, more or less closed economic complexes, in which everything necessary was produced, from tools of production to consumer products, naturally slowed down the development of commodity-money relations in the country, therefore, the possibility of the appearance in this era of a debt slavery is almost ruled out. It is possible that most of the Egyptian domestic slaves were descendants of those inhabitants of the Nile Valley, who were captured and enslaved by their neighbors during the period of fragmentation and wars between the nomes, and then between the two early Egyptian states. But, of course, there were some other ways of enslaving fellow tribesmen. So, high officials of the second half of the Old Kingdom, flaunting their virtue, boast in their autobiographical inscriptions that they have not enslaved a single Egyptian in their entire life. Consequently, the very possibility of enslaving fellow tribesmen – the inhabitants of the Nile Valley – was not excluded and did take place, but, obviously, enslaving them was considered reprehensible, and possibly prohibited by the royal authorities. It is not for nothing that indirect information about the enslavement of the Egyptians dates back mainly to the end of the Old Kingdom, when there was already a sharp decline in the central government.

There is no doubt that royal, temple and noble households were predominant in the economic structure of the Old Kingdom. However, were these large farms the only form of organization of production in the country, or could there exist a small but autonomous community-private sector of the economy outside of them? It is difficult to answer this question based on Egyptian sources of that era, since all of them are related only to the royal and noble households. Only on the basis of a few indirect data can it be assumed that such a sector probably existed. So, for example, one nobleman, who lived at the end of the III dynasty, buys land from a collective of certain nisu-tiu (“royal”), who, therefore, had some individual or collective rights to the land and could dispose of it at their own discretion. Maybe, the existence of small individual farms is evidenced by the inscriptions of the nobles of the end of the Old Kingdom, who, according to them, helped some, apparently small, producers with sowing grain and draft cattle during the plowing period. It is difficult to imagine that such assistance could be carried out within the framework of the tsarist and noble households, based, as we have seen, on completely different principles. Finally, weren’t the ruined small proprietors, becoming dependent on the owners of large noble farms, turning into slaves-baku? Were they not the source of the replenishment of such a large category of funeral priests, who provided the funeral cult of nobles? It is also possible that among the participants in the exchange market, known to us from tomb images, there were not only workers involved in large noble households, but also small individual producers. However, these are all just assumptions. The material is too insignificant and contradictory to draw any firm, unambiguous conclusions.

Social structure of the Old Kingdom

At the head of the established Egyptian state was a king, often called pharaoh in literature – a term that came from the Greek language, but goes back to the ancient Egyptian allegorical name of the king of the New Kingdom era – per-‘o, which meant “Big House” (ie palace) – the very name of the king was considered sacred, and it was forbidden to pronounce it in vain.

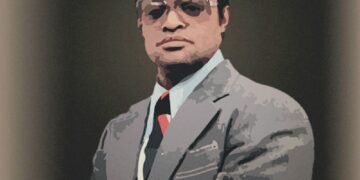

Pharaoh Mikerin with two goddesses

Pharaoh Mikerin (4th dynasty) with two goddesses – Hathor on the left, Bat on the right – the patroness of the 7th nome of Upper Egypt.

The Egyptian king had unlimited economic, political and supreme priestly power. All significant events in the country and abroad were carried out in the name of the pharaoh – large irrigation and construction work, the development of fossils and stones in the surrounding deserts, wars and trade expeditions, large religious and dynastic holidays. The king was revered as a god and was, according to Egyptian ideas, equal in everything to the gods and even surpassed them in power. So, during the heyday of the Old Kingdom, the tombs of the kings – the pyramids – overshadowed with their splendor the temples of the gods, at that time still very insignificant, so much so that almost nothing of the latter has survived to this day. The long, over time increasingly colored with epithets, the title of the Egyptian king contained five names, including the personal and the throne. Until the end of Egyptian history, the pharaoh acted as the king of Upper and Lower Egypt, which was recorded in his title as a memory of the once independent kingdoms of the North and South. A relic from the times of the two pre-dynastic kingdoms was the duplicated system of some government departments of the country.

The most important assistant to the tsar was the supreme dignitary – chati (in literature often called the vizier), who, on behalf of the tsar, carried out general management of the country’s economic life and the main court of justice. At different times, the chati could also hold some other major positions, in particular the position of the head of the capital’s administration. It is known, however, that during almost the entire history of Egypt he was not trusted with the leadership of the military department, headed by another major dignitary – the chief of the army.

Once independent nomes, having become part of a single state, turned into its local administrative and economic districts, and during the heyday of the Old Kingdom, during the 4th dynasty, complete subordination of the nomes to the central government was noted: the king could voluntarily move nomarchs (rulers of nomes) from from one nome to another, from Upper Egypt to Lower Egypt and vice versa, there was strict control of the center over all actions of the local administration. During the period of the 3rd and 4th dynasties, the highest metropolitan nobility consisted of a narrow circle of persons who were blood relatives with the king. The most important persons in the state – chats, military leaders, heads of various departments and works, high priests of the most important Egyptian temples – were close or more distant relatives of the royal house, the ruling dynasty. Centralized control was carried out with the help of a huge,

The only kind of permanent Egyptian army, which began to take shape during the early kingdom, was the infantry. The warriors were armed with bows, arrows and short swords. Often during campaigns, soldiers were transferred to the battlefield from their permanent locations on cargo river ships. The borders of Egypt in the North and South were protected by a chain of defensive fortresses, which housed military garrisons. It is interesting that the police functions in Egypt from ancient times were carried out by people from the early conquered by the Egyptians of Northern Nubia – the Majays.

Pyramid building

Egypt is often figuratively called the “Land of the Pyramids”. In the immediate vicinity of Cairo and to the south of it, these grandiose burial structures of the kings of the Old Kingdom are scattered, mute witnesses of the unprecedented power of the Egyptian rulers, called to forever glorify the names of the pharaohs buried in the underground chambers of these peculiar tombstones. The first, still stepped, 60-meter pyramid was erected near the modern town of Sakkara to the south of Cairo for the Pharaoh of the III Dynasty, the founder of the Old Kingdom of Jeser by a talented architect, doctor and chati, the famous Imkhetep, who was later deified. Unshakably stands in the suburb of Cairo, Giza, the first and only surviving of the seven wonders of the ancient world – the great pyramid of the second king of the IV dynasty Cheops (Khufu) – 146-meter high, composed of 2 million 300 thousand superbly fitted huge boulders. Here also rise the pyramids of his successors – the youngest son named Khefren (Khafra), which is only three meters lower than his father’s pyramid, and the 66-meter pyramid of another pharaoh of the same dynasty, whose name was Mikerin (Menkaure), which is significantly inferior to them. Each king of the Old Kingdom began to build a tomb for himself immediately after accession to the throne, and it was sometimes erected over several decades.Herodotus , who traveled through Egypt in the 5th century. BC, left us a vivid, but not entirely accurate description of the construction of the Cheops pyramid, as it was preserved in the memory of distant descendants.

Cheops, according to the stories of Herodotus, plunged the country into the abyss of disasters, forcing all the Egyptians to work for him. Some dragged huge blocks of stone from quarries in the eastern desert to the Nile, others loaded them onto ships and delivered them to the left bank of the Nile, others dragged them to the foot of the Libyan plateau to the construction site. One hundred thousand people worked there day after day, replacing each other every three months. For ten years, they built only the road along which they dragged the stones, and the burial crypt, for twenty years the pyramid itself was erected above them.

In fact, the building material for the construction of the pyramid was the local limestone, mined right there, at its foot, and only high-quality white limestone was brought from the opposite bank for facing the interior of the pyramid and its outer edges. The pyramid itself was erected by a limited number of working groups, consisting of permanent, qualified, specially trained workers. Special workers in brigades also worked in the neighboring quarries. There is no doubt, however, that a large volume of unskilled auxiliary labor was used in the construction of the pyramids, but this happened mainly during the floods of the Nile, when agricultural work was impossible, and therefore did not damage the economy. Next to the pyramids of the 4th dynasty, there is a 20-meter Great Sphinx carved into the rock – its face, disfigured by time, is believed to have a portrait resemblance to King Khefren, at the time of which, apparently, the Sphinx was sculptured. And nearby, near the pyramids, there is a large city of the dead – the burials of the nobility from the heyday of the Old Kingdom. The kings of the subsequent, V and VI dynasties also erected pyramids for themselves, although less grandiose. The pyramids of the 5th Dynasty are located in the region of Abu Sira and Sakkara. Near the last village are also the pyramids of the kings of the 6th dynasty. The Sakkar necropolis of the nobility is the most extensive and important in the Old Kingdom. there is a large city of the dead – the burials of the nobility during the heyday of the Old Kingdom. The kings of the subsequent, V and VI dynasties also erected pyramids for themselves, although less grandiose. The pyramids of the 5th Dynasty are located in the region of Abu Sira and Sakkara. Near the last settlement there are also pyramids of the kings of the 6th dynasty. The Sakkar necropolis of the nobility is the most extensive and important in the Old Kingdom. there is a large city of the dead – the burials of the nobility during the heyday of the Old Kingdom. The kings of the subsequent, V and VI dynasties also erected pyramids for themselves, although less grandiose. The pyramids of the 5th Dynasty are located in the region of Abu Sira and Sakkara. Near the last settlement there are also pyramids of the kings of the 6th dynasty. The Sakkar necropolis of the nobility is the most extensive and important in the Old Kingdom.

Military campaigns and foreign relations

The time of the Old Kingdom left us not so much the inscriptions of the kings as the autobiographical inscriptions of nobles and nomarchs, telling about military campaigns, trade expeditions, and the development of minerals outside of Egypt.

The founder of the IV dynasty, King Snefru, made a long campaign in Ethiopia, killing 7 thousand Nubians and taking 200 thousand heads of cattle, after a campaign in Libya, he brought 1100 Libyans and new herds to Egypt. In Sinai, the kings of the 5th dynasty Sahura and Unis fought against the Asian tribes. They also undertook campaigns in Libya. In the memorial temple of Sahur, for example, ships are depicted bringing captive Asians and Libyans to Egypt. From him, the first information about the journey of the Egyptians to the distant mysterious Punt , which was, possibly, on the territory of modern Somalia, reached us . At that time, the channel between the eastern arm of the Nile and the Red Sea had not yet been dug, so the journey had to begin in the city of Koptos in Upper Egypt, from where along the bed of the dried up river Wadi Hammamat The Egyptians walked to the coast, and then went on ships to Punt, bringing from there incense, myrrh, incense, and gold.

Military campaigns were also organized by the tsars of the 6th dynasty. Piopi I, the second king of the 6th dynasty, fought against the Asian tribes already outside the Sinai Peninsula, and the Egyptian troops moved both by land and sea. The son of Piopi I, Merenre, went to Ethiopia. Also organized were “economic” expeditions, the main purpose of which was the extraction of minerals and other types of raw materials (especially for the manufacture of luxury goods).

Numerous inscriptions left at the place of their activity by officials whom the tsar sent to the mines and quarries tell about the organization of these “peaceful” campaigns, about the struggle against steppe cattle breeders on the way, about victories over them, about the development of minerals. The Egyptians still mined copper in the Sinai mountains, and turquoise was also mined there. The stone was everywhere, but rare rocks were sometimes delivered from afar. Lapis lazuli, for example, got to Egypt from the territory of modern Afghanistan through a multistage exchange. Numerous expeditions were outfitted on the eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea behind the Lebanese cedar. Ebony, ivory, skins of lions and leopards were brought from Nubia, but there is still no information about Nubian gold, the placers of which were subsequently intensively developed by the Egyptians.

Internal situation of the state

The internal position of the state of the Old Kingdom, despite its indisputable power, was, however, not serene. For some reason, the time of the reign of the III dynasty is shrouded in deep darkness – we only know well its founder Dzheser. The unfinished pyramid and the broken statues of Cheops’ son, Djedefr, perhaps testify to the internecine struggle between the two brothers, which ended in the victory of Khafre. Hidden from us, apparently, is the dramatic end of the powerful IV dynasty and the coming to its place of the V dynasty in the person of its founder Userkaf. The accession to the throne of this dynasty led to serious ideological changes associated with the beginning of the nationwide veneration of the sun god Ra – the main god of the Heliopolis nome, from which, possibly, the 5th dynasty originated. Now in the title of the king is not only identified with the god Horus, traditional patron saint of early dynastic Egyptian kings, but also acts as the son of the god Ra. The five first kings of the new dynasty erect solar temples with a huge obelisk inside a fenced yard in honor of the god Ra. During the 5th dynasty, great internal political shifts also took place, the external expression of which was the appearance among the highest officials of the state of people from the nobility who were not related to the king by kinship (which was so typical during the previous dynasty).

Finally, the entire second half of the Old Kingdom is a time of an invisible, but long and stubborn struggle of the strengthened nominee administration against the excessive dominance of the central government, for its political and economic autonomy. There is no direct written evidence of this struggle, yes, it may not have been, but much can be understood if we look at least at the burials of the Upper Egyptian nomarchs (heads of nome administrations) of the 6th dynasty. Hereditary necropolises of nomarchs of that time are found throughout Upper Egypt. And we see that the tombs of the nomarchs from generation to generation are becoming more and more luxurious, especially the tombs of the nomarchs of the richest regions, and the tombs of the kings – the pyramids – can no longer be compared with the majestic structures of the powerful pharaohs of the IV dynasty.

Gradually, the nomes undermine the power of the central government, and the tsarist administration, over time, more and more has to make concessions to their rulers. There is a redistribution of the material and human resources of the country in favor of the nomes, to the detriment of the center. The economic power of the Memphis kings is undermined, their political influence is weakening. Soon after the death of the king of the 6th dynasty, Piopi II, who reigned in Egypt for almost 100 years, Memphis’s power over Egypt becomes nominal. The 7th-8th dynasties still support the traditions of the Old Kingdom, but the era of former greatness has passed irrevocably. Around 2400 BC the country is divided into many independent nomes. The era of the Old Kingdom ends.