The train crawled like a turtle, and it took three whole days to cover 300 miles from Chisinau to Bucharest. The weather was getting worse every day, and in the last 24 hours alone, six inches of snow fell. On November 18, 1916, British Major John Norton-Griffiths got up at 6 a.m., shaved with ice cold water and waited. After two weeks’ journey from London, the major, in his own words, felt like a boiled owl. The Romanian capital was only 10 miles away, and beyond it, to the north, lay oil reserves that should not have fallen into the hands of the Germans.

From the Royal Guard to the Royal Engineers Corps

John Norton-Griffiths was without a doubt a legendary figure. He was born in Somerset on July 13, 1871, did not differ in his youthful behavior and perseverance, and at the age of 16, adding to his age, he became a private in the Regiment of the Royal Horse Guards. A year later, he managed to resign from military service thanks to bribes and contacts from the father of his school friend Percy Kimber – Member of the British Parliament and owner of a colonial company in Natal, Sir Henry Kimber decided to send his son to learn about life in South Africa, but did not want to let him go alone.

In the colonies, Norton Griffiths spent 12 years. He moved from Natal to the Transvaal, where he first grazed sheep, then mined gold in mines, managed a mine, participated in the Jameson raid and suppressed the Matabele uprising, was awarded a medal and mentioned in the order. In January 1900, Norton Griffiths was recommended to Field Marshal Sir Frederick S. Roberts, Earl of Roberts of Kandahar, and as Field Marshal’s adjutant and chief of personal security, John Norton-Griffiths served throughout the Boer War .

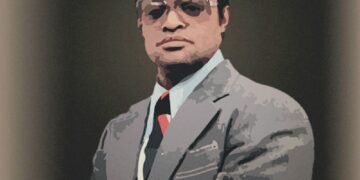

Major of the Corps of Royal Engineers John Norton-Griffiths. London, 17 October 1918 (National Portrait Gallery) – The Man Who Stripped the Kaiser’s Oil | Warspot.ru

In 1901, Norton Griffiths received a contract to build a gold mining enterprise on the Ivory Coast, and then implemented projects around the world: in Angola, Canada, Australia, Chile and even in Baku, on the southern outskirts of the Russian Empire. He had obvious engineering and entrepreneurial talent, made influential friends, and in 1910 was elected from the Tory party to the House of Commons of the British Parliament.

When Europe smelled of gunpowder, Norton-Griffiths once again drastically changed his life. Three days before Britain’s entry into World War I, he advertised in the newspapers, calling everyone who knew him from South Africa under the banner of his volunteer corps. There were many volunteers, and on August 24, 1914, Major Norton-Griffiths’ detachment officially became King Edward’s 2nd Cavalry Regiment. All costs – 40 thousand pounds sterling (about 3.8 million in 2018 prices) – were paid by the newly made regiment commander out of his own pocket. However, Norton-Griffiths did not serve in the cavalry for long – the command found his talents more suitable for use in the Royal Engineers Corps.

“Moles” and ammonal

At half past ten in the evening on December 20, 1914, the positions of the British Sirhind Brigade at Givenchy-le-la-Bassé were blown up by a dozen 50-kg underground charges. The losses in the explosion and during the subsequent attack of the Germans amounted to about 800 people who arrived at the front just 11 days ago. A month later, the German army had already deployed 20 charges near Kuyenshi, and on February 3, when the underground gallery dug by the Germans was blown up, it suffered heavy losses and the 3rd battalion of the East Lancashire regiment was thrown back. A week later, the same fate befell the 11th hussar and 16th uhlan regiments. It became clear that the Germans were winning the underground war , and the British urgently needed a decent response.

Norton Griffiths (right) and his Rolls Royce, which always had a supply of whiskey, wine, champagne and port in its trunk to encourage unit commanders not to interfere with the transfer of their soldiers to tunnel companies. France, 1915 – The Man Who Deprived the Kaiser of Oil | Warspot.ru

The solution was found with Major Norton-Griffiths, who, back in 1913, received contracts for the reconstruction of the sewer systems of Manchester and Liverpool and managed to get to know closely the laying of tunnels. Now it was he who was entrusted with overseeing the formation of the tunnel companies, in which many of his former employees were enrolled. In search of specialized specialists, Norton Griffiths traveled all over the front, negotiating with the unit commanders about the transfer of those who had experience working underground – primarily coal miners – to the Royal Engineers Corps.

The presence of “moles” from tunnel companies on the front line had the most positive effect on the morale of the soldiers in the trenches – at least, now there were professionals in their field next to them, able to distinguish the rustles of the ubiquitous rats from the Germans digging an underground gallery.

Major Norton-Griffiths ‘duties included not only the selection of personnel for the underground war: it was easier to find specialists than modern materiel – the Royal Engineers’ Corps intended to equip the tunnel companies with the tools carefully preserved by the logisticians since the Crimean War. The worst of all was, oddly enough, with explosives: Norton-Griffiths’ attempts to get ammonal from the warehouses of the V corps first crashed against the impeccable logic of the army bureaucracy in the person of the corps intendant:

“I have consulted with the senior physician of the corps. He explained to me that Ammonal is a compounding drug, widely used in America as a sedative in cases of abnormal sexual arousal … To date, the senior physician points out, there have been no cases among the Corps personnel requiring the use of this drug.

Of course, in the end, ammonal was transferred from the category of medical preparations to the class of explosives, and already in 1915 the tunnel companies managed to successfully carry out a number of high-profile operations in all respects. The culmination was the detonation of 19 underground charges on July 1, 1916, on the first day of the fighting on the Somme . However, by that time, Norton-Griffiths was no longer in France – on March 30, he left for London, where he received a position in the Ministry of Ammunition. It must be admitted that many at the front were happy to get rid of the overly energetic major, whose ability to achieve results, regardless of the army hierarchy, created significant tension.

Romanian false start

By the end of the summer of 1916, the Entente had problems with Romania – more precisely, with its oil and oil industry.

It took the Romanian ruling dynasty of the Hohenzollerns two whole years to decide on which side to go to war. Yes, there was an allied treaty between Romania and Austria-Hungary, but the chances of victory for the Entente countries seemed great to the Romanians. When the Entente ambassadors in Bucharest promised to give Romania Transylvania to Romania during the post-war division of Europe, the last doubts disappeared, and on August 27, 1916, the Kingdom of Romania entered the war against the Central Powers.

Alas, the Romanian army did not succeed in a swift, sweeping victorious thrust on Hungary. On September 1, the troops of Field Marshal August von Mackensen counterattacked in Dobrudja, and the offensive in Transylvania had to be stopped. Under the onslaught of German, Austrian, Bulgarian and Turkish troops, the Romanian army began to withdraw, but the Central Powers did not intend to stop at the pre-war border of Romania. This is where the oil issue arose.

Lifting oil with a manual gate from a well in a field near Ploiesti. Prahova County, Romania, early 20th century – The Man Who Deprived the Kaiser of Oil | Warspot.ru

One of the first descriptions of an oil field on the territory of modern Romania dates back to 1716 and belongs to the pen of the Moldavian prince Dmitry Cantemir:

In the 19th century, oil found a better use than lubrication for the wheels of peasant carts, and in 1857 Romania was the first in the world to overcome the milestone of 250 tons of annual production. The United States reached this mark in 1859, Italy in 1860, Canada in 1862, Russia in 1863. In 1900, Romania became the first exporter of gasoline in the world, and by the beginning of the First World War, production was 1,885,619 tons. About a million tons of oil and petroleum products went to Germany, providing two-thirds of all its fuel needs. On the other hand, German companies have done a lot to make the Romanian oil industry dependent on financial injections and equipment supplies from Germany.

German Quartermaster General Erich Ludendorff assessed the importance of Romania’s resources for his country: “We cannot exist, let alone win the war, without Romanian bread and oil . ” The seizure of oil and oil fields became for the Central Powers, without any exaggeration, a matter of life and death.

Interlude at Constanta

On October 19, 1916, the troops of Field Marshal von Mackensen in Dobrudja resumed the offensive, which had been suspended a month earlier, in the strip between the Danube and the Black Sea. The very next morning they entered the zone of action of the main guns of the Russian battleship Rostislav, which opened fire from the port of Constanta. Despite the raids of German airplanes, the battleship, destroyers and minesweepers of the Special Forces of the Russian Black Sea Fleet were able to delay the enemy’s advance, but it was already impossible to reverse the situation. On the night of October 21, the evacuation of the civilian population of Constanta began, and the commander of the Detachment, Rear Admiral P.I. Patton-Fanton-de-Verrion reported to the commander of the fleet, Vice-Admiral A.V. Kolchak, that a critical situation has developed at the front, and there is no hope for the 19th division of the Romanians. In response, Kolchak ordered the Detachment to leave Constanta,“When it will be impossible to hold on . “

At about one o’clock in the afternoon on October 22, Russian ships went to sea, evacuating all the property of the base. Nevertheless, in accordance with the order of the Supreme Commander-in-Chief, all reserves of oil and oil products were left untouched in Constanta, since the Russian Headquarters very optimistically believed that the port would soon be recaptured by a counter-offensive of Russian troops. According to Romanian sources based on the materials of the German commission, 238 thousand tons of gasoline, diesel fuel, kerosene and oil fell into the hands of von Mackensen’s soldiers. It took several days for it to become clear at the Russian Headquarters that it would not be possible to return Constance, and all the port reservoirs, along with their contents, must be destroyed.

For several days this task could not be solved due to stormy weather, but on November 1 and 4, the cruiser Memory of Mercury successfully fired at Constanta, firing 106 and 231 6-inch shells, respectively. During the second voyage, the ship managed to achieve serious results – according to German data, 15 of 37 tanks were destroyed in the port, the fire could not be extinguished for several days, and the smoke cloud was visible from a distance of 70 miles. But, despite the impressive picture, the Germans lost only 7% of all reserves.

With the fall of Constanta, the last hopes of the Entente to export from Romania oil and oil products, which the Germans so desperately needed, melted away. It already seemed that soon the “big prize” itself – the Romanian fields and oil refineries – would be in the hands of the enemy.

Sodom and Gomorrah near Ploiesti

On October 31, the military committee of the British Cabinet of Ministers discussed the situation in Romania. A decision was made, worthy of an immortal, “So do not get you to anyone!” from the play by A.N. Ostrovsky – it was impossible to allow the capture of the Romanian oil fields by the Germans, and if necessary, oil reserves, oil wells and oil refineries had to be destroyed at any cost.

On November 4, the director of British military intelligence, George MW Macdonogh, assigned the task to Major Norton-Griffiths, who immediately sailed to Norway, and from there, via Sweden and Finland, reached Petrograd by November 12. Instructions, received from the Chancellor of the Treasury, Reginald McKenna, gave him virtually unlimited powers to destroy Romanian oil reserves and oil facilities owned by British shareholders. In turn, the British government undertook an obligation after the end of the war to pay the owners in full the cost of restoring all destroyed property.

By November 14, Norton Griffiths had already left Kiev and Chisinau behind, but as the Romanian border approached, the speed of advance began to decline. There was no food on the train, and the stock of chocolate kept from London had to be printed out. The train did not arrive in Bucharest until November 18, but it soon became clear that the railway workers worked even faster than the Romanian government officials. Almost a week was spent on meetings with various responsible persons and an assessment of the situation, and on November 23, the Romanians and the French created a special commission on oil issues, and the matter generally got up.

Meanwhile, the situation at the front became more and more difficult: on November 11, German troops broke through the passes of the Transylvanian Alps and reached the plains of Oltenia in southwestern Romania. The fall of the Romanian capital was only a matter of time, and the speed of the enemy’s advance was much more influenced not by the fierce resistance of the Romanian troops, but by the snow covering mountain roads and trails. The evacuation of Bucharest began on 25 November.

In these circumstances, Norton-Griffiths decided to take matters into his own hands – to his subordinate Captain J. Pitt, he ordered the destruction of grain reserves, and he himself took up oil. The Romanian government was unable to provide the major with transport, but Prince Gheorghe-Valentin Bibescu, an automotive and aviation enthusiast, and the future president of the International Aviation Federation, helped with the cars. Together they traveled to the Ploiesti region, where the main production and refining capacity of Romania was concentrated – on an area of 1000 km² there were more than 2000 oil wells and a significant number of oil refineries with about 1000 oil reservoirs.

On November 26, Norton Griffiths began operations in Targovishte, the ancient capital of Wallachia. Members of the Franco-Romanian oil commission tried to protest and even arrested the manager of the largest oil refinery in the city, British citizen William Guthrie, who expressed his readiness to assist in the destruction of the plant entrusted to him. Major Norton-Griffiths was not stopped by these obstacles: within a few days, all objects in Targovishte were destroyed.

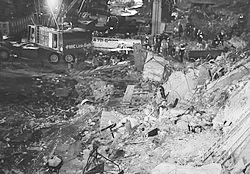

Then everything repeated itself in the Ochiuri Razvad region, at the largest Romanian field in Moreni, in Filipesti de Padure, at 13 oil refineries in Ploiesti, at 66 wells in Beiko – and then in Campina, in Bustenari and six more places with difficult to pronounce Romanian names. The whole work took about 20 days. 1677 wells were destroyed, including 1047 producing ones, and about 830 thousand tons of oil and oil products were burned. For comparison – from oil spills and burning of wells during the war in the Persian Gulf in 1991, from 270 to 820 thousand tons were lost.

Norton Griffiths, who arrived in chaotic Romania with only one orderly, quickly and efficiently organized the work of the Romanian and British officers assigned to him, as well as groups of local workers. He did not know the Romanian language, the nuances of big politics, local and industry specifics, but he was technically savvy and had tremendous willpower – by persuasion and threats, he mobilized engineers and workers to destroy what had been created over the years.

A system for the destruction of production facilities was developed: the towers were destroyed, the wells were tightly sealed with drilling equipment dropped into them, drive mechanisms, generators, pipelines, machinery and laboratory equipment were smashed with sledgehammers. Oil was pumped out of huge tanks into specially dug ditches and set on fire – it burned, covering everything around with black choking smoke, and during the day it was as dark as night.

Major Norton-Griffiths has always been in the thick of things. In Moreni, he was stunned by an explosion, and he would have burned up along with the oil, if he had not been pulled out by Prince Bibescu. Members of the Franco-Romanian Oil Commission tried to arrest Norton-Griffiths, but he cleared his way with his fists. Acting in the strip already abandoned by the Romanian units, he twice had to break away from the patrols of the German cavalry in cars. The cars got stuck behind Braila, and they had to be left, but a cavalry regiment of the Russian army passing by gave him and his companions spare horses – they were used by Norton-Griffiths to reach the troops of King Ferdinand I, who took command of the newly formed Romanian Front, by Christmas.

Epilogue

The activities of Major Norton-Griffiths’ group dealt a severe blow to the plans of Germany, which was able to start production in the Romanian fields only six months after the capture of the country. In 1917, oil production in Romania was only one third of the level of 1914, in 1918 – 80%. Quartermaster General Ludendorff admitted that the destruction of the oil facilities near Ploiesti “significantly limited the supply of oil to our army and country . “

Norton-Griffiths himself did not feel the ecstasy of destruction, and therefore did not like to remember his mission in Romania. However, his efforts were highly appreciated by the Allies in the Entente: in the next two years he became a knight-commander of the British Order of the Bath, an officer of the French Order of the Legion of Honor, a Commander of the Order of the Star of Romania and a Chevalier of the Russian Order of St. Vladimir, 3rd degree.

After the war, a joint Anglo-Romanian commission estimated the damage done to the Romanian oil industry by the people of Norton Griffiths at £ 10 million (more than £ 500 million at current prices). Romania did not receive a single penny of this amount, since Great Britain put forward a counter demand to pay for the weapons and ammunition supplied during the war years in the total amount of 40 million pounds.

In 1924, after 14 years in the House of Commons, Norton-Griffiths left the UK Parliament and focused on running his own company. Five years later, when the Egyptian government decided to increase the height of the Aswan Dam, a contract for this work was signed with Norton Griffiths. However, unforeseen difficulties soon arose: the company said that government inspection engineers were of little competence, and the Egyptians replied that Norton-Griffiths did not cope with financial obligations under the contract, and work was behind schedule.

In September 1930, the Aswan project was stopped. On September 27, Sir John Norton-Griffiths left the Alexandrian hotel and, taking a small boat, set out for a cruise in the Mediterranean. After some time, the boat was found empty, and soon after the search began, the body of Norton-Griffiths was also found. Examination showed that death occurred as a result of a gunshot wound to the temporal region of the head. The forensic investigation concluded that the man who deprived the Kaiser of the Romanian oil had committed suicide. He was 59 years old.